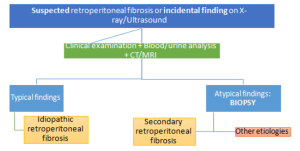

IMAGING

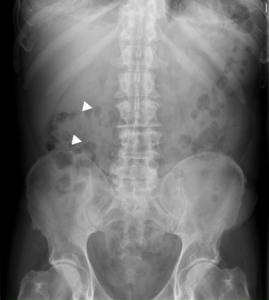

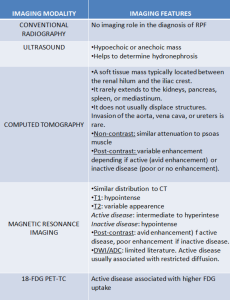

PLAIN X-RAY

Conventional radiographs have no imaging role in the diagnosis of RPF [7].

ABDOMINAL X-RAY

Inespecific. In advanced stages, a central mass of soft tissue at the level of the psoas line is sometimes seen.

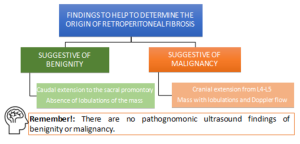

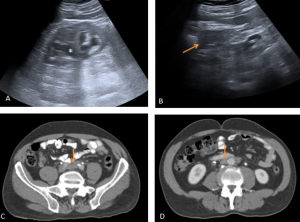

ULTRASONOGRAPHY (US)

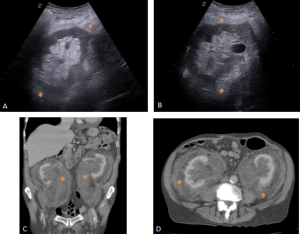

Useful as screening, but with low sensitivity.

RPF is visualized as a hypo or anechoic, irregular demarcated retroperitoneal mass, anterior to the lower lumbar spine or the promontory of the sacrum.

If ureteral entrapment is present, ureterohydronephrosis may occur in varying degrees.

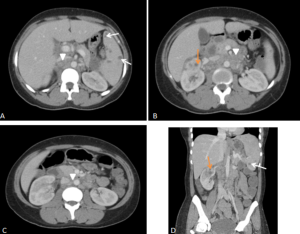

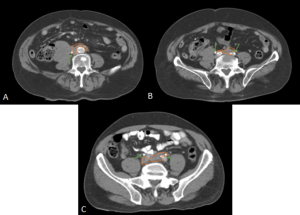

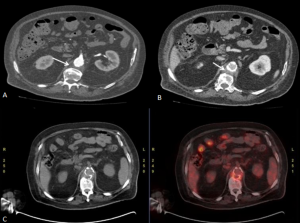

MULTIDETECTOR COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY (MDCT)

Useful to assess other conditions associated with RPF (IgG4 related diseases such as autoimmune pancreatitis or biliary structures ductal dilation).

MDCT may fail to demonstrate abnormalities in approximately one third of surgically proven RPF cases.

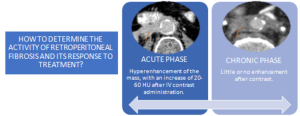

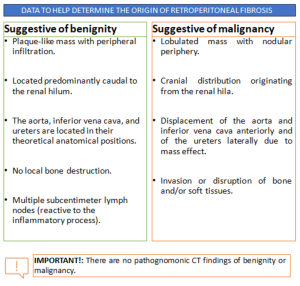

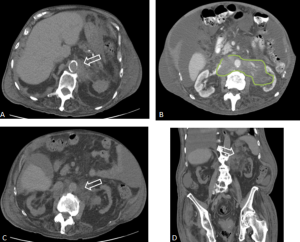

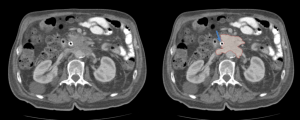

RPF typically appears as a well-defined, irregular paraspinal soft-tissue mass, isodense to the psoas muscle and without lateral extension beyond it. Most often centred at L4–L5 near the aortic bifurcation, it may extend cranially towards the renal hila or, less commonly, caudally to involve pelvic structures. Baseline Hounsfield units (HU) values and the diameter of the retroperitoneal tissue can assist in assessing inflammatory activity. [1,3,5-8]

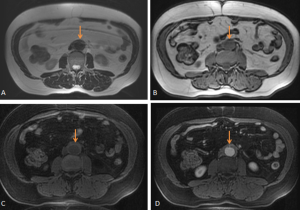

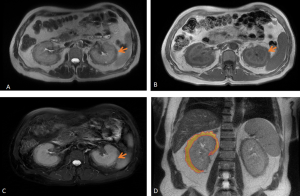

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING (MRI)

MRI offers superior soft-tissue contrast and enables non-contrast visualisation of the renal collecting system, making it particularly valuable in patients with renal impairment.

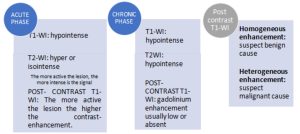

RPF is typically hypointense on T1-weighted images with variable intensity on T2-weighted images as well as in apparent diffusion coefficient values depending on the degree of active inflammation [2,3].

NUCLEAR IMAGING

FDG-PET/CT enables reliable assessment of metabolic activity in idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis, supporting diagnosis, treatment monitoring and prognostic stratification. Increased FDG avidity is associated with active disease and may predict response to immunosuppressive therapy, while metabolically inactive tissue can guide ureteric stent removal. Although CT and MRI remain the preferred modalities for routine follow-up, FDG-PET/CT is valuable when residual disease activity is uncertain. Higher SUVmax and contrast-enhancement scores correlate with inflammatory markers, with SUVmax > 2.76 accurately identifying active disease.

BIOPSY

Biopsy is indicated when RPF is suspected on clinical, laboratory, or imaging findings, and is particularly crucial in cases with atypical anatomical distribution or inadequate therapeutic response. Histopathological evaluation enables distinction between IgG4-related and non-IgG4-related variants of the disease.

CASES

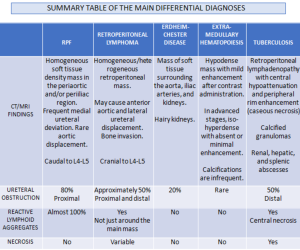

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES

RETROPERITONEAL LYMPHOMA

Lymphoma is the most common malignant retroperitoneal lesion, being either a Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

CT typically shows a homogeneous, well-defined, bulky mass displacing anteriorly but not compressing adjacent retroperitoneal structures. Superior extension above L4–L5 is more frequently observed. Post-contrast CT usually demonstrates homogeneous enhancement, although peripheral or heterogeneous enhancement may occur in the presence of necrosis.

On MRI tends to be isointense on T1-weighted imaging and iso- to hypointense on T2-weighted sequences, with moderate and often heterogeneous enhancement after contrast administration.

Although enhancement may be present in both malignant and idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis, a hypointense T2 signal is far more suggestive of chronic or inactive idiopathic RPF. Differentiation on FDG-PET/CT can also be challenging; however, malignant aetiologies typically demonstrate higher FDG avidity and greater SUVmax values. In comparative studies, lymphoma and metastatic disease showed substantially higher metabolic activity than idiopathic RPF, and were more frequently associated with lymphadenopathy at distant nodal stations [3].

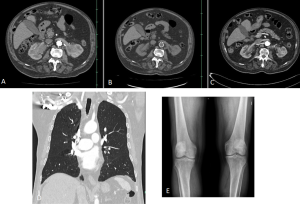

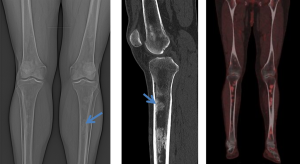

ERDHEIM-CHESTER DISEASE (ECD)

ECD is a rare non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis affecting multiple organ systems, typically presenting in adults in their 5th–7th decades with slight male predominance.

Diagnosis relies on biopsy supported by characteristic clinical and imaging features.

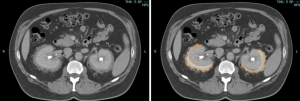

Retroperitoneal and renal involvement occurs in a significant proportion, with CT and MRI demonstrating bilateral perinephric and posterior pararenal soft-tissue infiltration, producing the classic “hairy kidney” appearance. Infiltrates are generally isoattenuating or iso- to hypointense to skeletal muscle with mild contrast enhancement; FDG uptake may be present but can be obscured by physiological renal activity. Chronic infiltration may result in renal atrophy.

Although both ECD and retroperitoneal fibrosis can lead to hydronephrosis, their distribution differs: ECD typically affects the perinephric fat and renal hila, whereas idiopathic RPF encases the anterolateral aorta and proximal ureters. Aortic encasement (“floating aorta sign”) and periureteric involvement may occur, but ECD usually spares the IVC and pelvic ureters. Additional distinguishing features include irregular perirenal infiltration and bilateral symmetric adrenal thickening.

Skeletal involvement, particularly of the femur, tibia and fibula, is seen in most patients, often causing bone pain [9].

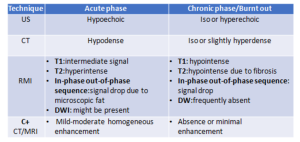

EXTRA-MEDULLARY HEMATOPOIESIS (EMH)

EMH is often incidental and represents compensatory blood cell production outside the bone marrow as a compensatory mechanism for [10]:

- Decreased bone marrow hematopoiesis or increased peripheral destruction of blood cells.

- Secondary to bone marrow infiltration.

Although most cases present microscopically with homogeneous hepatosplenomegaly, macroscopic EMH may appear at several sites, including the thorax (most commonly as paraspinal masses), liver and spleen, and retroperitoneum, where it commonly appear as unilateral or bilateral soft-tissue masses, frequently involving the perinephric space [11]. These lesions typically form a soft-tissue rind without renal mass effect, with foci of fat-attenuation may be interspersed within the regions of soft tissue, and are hypovascular on post-contrast imaging. Calcifications are uncommon.

The characteristic perinephric distribution generally distinguishes EMH from retroperitoneal fibrosis, though differentiation becomes difficult when RPF exhibits atypical peri-renal extension. Supporting features such as hepatosplenomegaly or skeletal abnormalities related to the underlying haematological disorder (e.g., sclerotic bone in myelofibrosis or “H-shaped” vertebrae in sickle-cell disease) aid in establishing the correct diagnosis.

Depending on the phase, we will observe different radiological characteristics:

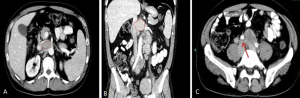

RETROPERITONEAL METASTASIS AND ADENOPATHIES

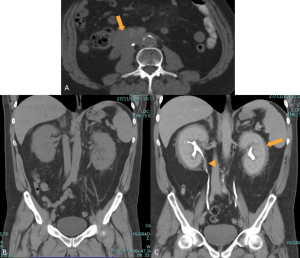

Some tumors, such as prostate, cervical, breast, and lung cancer, can present with retroperitoneal metastases that manifest as:

- A cuff of soft tissue along with a desmoplastic response, similar to retroperitoneal fibrosis.

- Usually more focal or asymmetric compared to retroperitoneal fibrosis.

- Signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences is higher and more heterogeneous.

- Additional lymphadenopathy also present in the pelvis and retroperitoneal region.

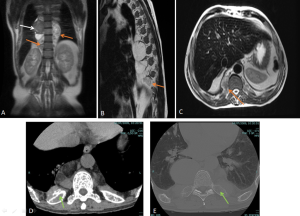

TUBERCULOSIS

The most common focus of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis is the abdomen. Abdominal tuberculosis frequently involves liver, spleen, genitourinary tract and retroperitoneal lymph nodes and retroperitoneal abscess as extension from adjacent spinal disease [3, 12, 13].

- Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy often appear with central hypoattenuation and peripheral rim enhancement on CT, suggestive of caseous necrosis.

- Hepatosplenic involvement may be micronodular or macronodular, with CT and MRI appearances overlapping metastases or abscesses; calcified granulomas can aid diagnosis.

- Genitourinary tuberculosis commonly affects the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and prostate, usually unilaterally. Renal findings include parenchymal oedema and hypoperfusion manifesting on CT as geographic areas of parenchymal hypoattenuation that mimic acute pyelonephritis and abscess (acute tuberculous renal abscess are 10-40 HU with mild peripheral enhancement) in the active inflammation, calyceal erosions, papillary necrosis, parenchymal cavitation, and calcifications in the chronic phase, potentially progressing to autonephrectomy. Ureteric involvement presents as wall thickening and strictures, predominantly in distal segments, leading to hydroureteronephrosis.