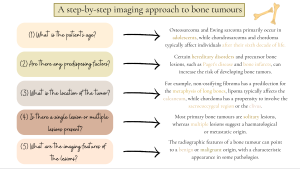

When faced with a bone tumour, one can consider several aspects in a step-by-step approach to increase diagnostic accuracy.

A systematic approach for the most common benign and malignant tumors is presented below:

I. Chondrogenic tumors:

- Osteochondroma

Fig 4: A step-by-step approach to osteochondroma.

Fig 4: A step-by-step approach to osteochondroma. - Enchondroma

Fig 5: A step-by-step approach to enchondroma.

Fig 5: A step-by-step approach to enchondroma. - Chondrosarcoma

Fig 6: A step-by-step approach to chondrosarcoma.

Fig 6: A step-by-step approach to chondrosarcoma.

II. Osteogenic tumors:

- Osteoid osteoma

Fig 9: A step-by-step approach to osteoid osteoma.

Fig 9: A step-by-step approach to osteoid osteoma. - Osteosarcoma

Fig 10: A step-by-step approach to osteosarcoma.

Fig 10: A step-by-step approach to osteosarcoma.

III. Vascular tumors:

- Hemangioma

Fig 11: A step-by-step approach to vertebral hemangioma.

Fig 11: A step-by-step approach to vertebral hemangioma.

IV. Osteoclastic giant cell-rich tumours:

- Aneurysmal bone cyst

Fig 12: A step-by-step approach to aneurysmal bone cyst.

Fig 12: A step-by-step approach to aneurysmal bone cyst. - Non-ossifying fibroma

Fig 13: A step-by-step approach to non-ossifying fibroma.

Fig 13: A step-by-step approach to non-ossifying fibroma. - Giant cell tumor

Fig 14: A step-by-step approach to giant cell tumor.

Fig 14: A step-by-step approach to giant cell tumor.

V. Notochordal tumors:

- Chordoma

Fig 15: A step-by-step approach to chordoma.

Fig 15: A step-by-step approach to chordoma.

VI. Other mesenchymal tumors:

- Simple bone cyst

Fig 16: A step-by-step approach to simple bone cyst.

Fig 16: A step-by-step approach to simple bone cyst. - Fibrous dysplasia

Fig 17: A step-by-step approach to fibrous dysplasia.

Fig 17: A step-by-step approach to fibrous dysplasia.

VII. Hematopoietic neoplasms:

- Multiple myeloma

Fig 19: A step-by-step approach to multiple myeloma.

Fig 19: A step-by-step approach to multiple myeloma.

VIII. Undifferentiated small round cell sarcoma:

- Ewing sarcoma

Fig 21: A step-by-step approach to Ewing sarcoma.

Fig 21: A step-by-step approach to Ewing sarcoma.

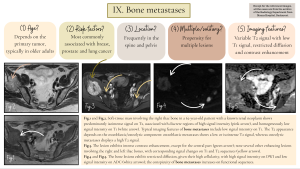

IX. Bone metastases

Several other types of bone tumors are briefly illustrated below:

- Chondromatosis

Fig 7: Other types of chondrogenic tumors.

Fig 7: Other types of chondrogenic tumors. - Chondroblastoma

Fig 7: Other types of chondrogenic tumors.

Fig 7: Other types of chondrogenic tumors. - Juxtacortical chondroma

Fig 8: Other types of chondrogenic tumors.

Fig 8: Other types of chondrogenic tumors. - Atypical cartilaginous tumor

Fig 8: Other types of chondrogenic tumors.

Fig 8: Other types of chondrogenic tumors. - Lipoma

Fig 18: Other types of mesenchymal tumors.

Fig 18: Other types of mesenchymal tumors. - Hibernoma

Fig 18: Other types of mesenchymal tumors.

Fig 18: Other types of mesenchymal tumors. - Plasmacytoma

Fig 20: Other types of hematopoietic tumors.

Fig 20: Other types of hematopoietic tumors. - Other types of bone metastases

Fig 23: Other types of bone metastases.

Fig 23: Other types of bone metastases. - Liposclerosing myxofibrous tumor

Fig 24: Other less typical scenarios of bone tumors.

Fig 24: Other less typical scenarios of bone tumors. - Aggressive hemangioma

Fig 24: Other less typical scenarios of bone tumors.

Fig 24: Other less typical scenarios of bone tumors.

Key information worth knowing about bone tumours:

1. Understanding the histopathological classification of bone tumours and briefly acknowledging the general morphopathological features of each tumour type helps recognise them on imaging.

2. The location of the lesion in the bone itself represents an essential clue for narrowing the differential diagnosis of bone tumors, such as:

- the bone portion involved: epiphysis/metaphysis/diaphysis;

- the location within the bone: intramedullary (eccentric/central), intracortical, periosteal (associating periosteal reaction) and parosteal.

For example, a non-ossifying fibroma is typically located eccentrically in the metaphyseal region of long bones, but can migrate towards the diaphysis secondary to bone growth.

3. It's important to note that chondrosarcomas can develop from preexisting enchondromas (central secondary chondrosarcomas) or osteochondromas (peripheral secondary chondrosarcomas), and distinguishing them radiologically is not always straightforward. However, certain aggressive features can indicate malignant transformation: a size > 5 cm, periosteal reaction, cortical disruption, or endosteal scalloping affecting > 2/3 of the cortical thickness (for enchondromas), and a cartilage cap thickness > 2 cm in adults or 3 cm in children (for osteochondromas).

4. In aneurysmal bone cysts, the name can be confusing: the term "aneurysmal" has its origin from the expansion of the affected bone, while "cyst" refers to the intrinsic fluid-filled cavities, but in fact, it actually represents a true neoplasm.

5. Non-ossifying fibromas represent the most encountered incidental bone lesion in children and adolescents, exhibiting a self-limiting course with variable imaging appearances which can sometimes lead to confusion; understanding the four stages of evolution by Ritschl aids in comprehending their different imaging appearances.

6. The "rising bubble sign" defined by the presence of locules of gas within the most non-dependent portion of a bone cyst in the case of an associated pathological fracture is known to be pathognomonic for a simple bone cyst, the fluid component of the cyst determining the gas to migrate upwards.

7. In Ewing sarcoma, the most common symptom is represented by local pain secondary to involvement of the periosteum, which is highly innervated, and systemic symptoms may also appear, potentially mimicking an infectious process.

8. On CT scan, measuring the HU units of a sclerotic bone lesion can help differentiate an enostosis from an untreated osteoblastic metastasis. A mean attenuation >885 UH or a maximum attenuation >1060 UH suggests an enostosis.

9. One of the most essential task when evaluating a bone tumour is recognising "don't touch" lesions, which represent bone lesions with typical imaging findings suggestive of a benign origin, with no further investigation or intervention needed, including non-ossifying fibroma, simple bone cyst, fibrous dysplasia, intraosseous lipoma, hibernoma, etc.

10. Tumor mimics are also of great importance when dealing with a potentially bone tumor and represent a comprehensive subject: knowing the imaging features of a bone marrow island, osteomyelitis, synovial herniation pit, subchondral cyst, stress fractures, or myositis ossificans helps, along with the clinical presentation, to differentiate between proliferative and non-proliferative lesions.