ANATOMY RELATED DISORDERS

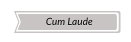

Patella alta refers to a superiorly positioned patella, resulting in delayed engagement with the trochlear groove during knee flexion and predisposing to patellofemoral instability and dislocation[3].

Patella baja, describes an inferiorly positioned patella, most commonly seen in post-traumatic or post-operative knees. It may lead to anterior knee pain, reduced range of motion, altered patellofemoral mechanics[1].

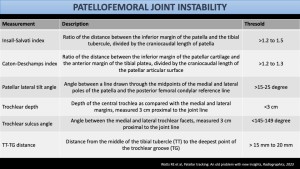

Both conditions can be evaluated using the Insall–Salvati or Caton–Deschamps index[1,2].

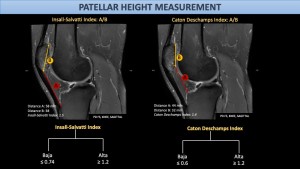

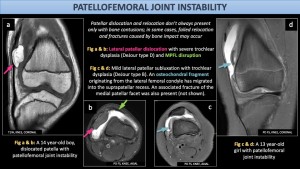

Patellar tracking and patellofemoral joint instability:

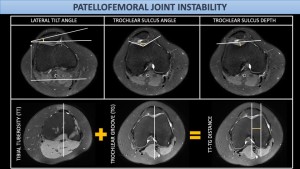

The convex posterior surface of the patella articulates with the concave trochlear groove during knee flexion. Patellar stability is provided by muscular, ligamentous, and bony structures, with the two primary stabilizers; the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) and the trochlear groove. From 0–30° of flexion, the MPFL is the main restraint against lateral patellar subluxation, whereas beyond 30° major stabilizer is the bony containment of the trochlear groove[2]. Trochlear groove morphology described by DeJour Classification.

Insufficient stabilizing mechanisms predisposes patients to patellofemoral joint instability. It most commonly affects adolescents and young adults and is therefore clinically relevant in an active population[2,4].

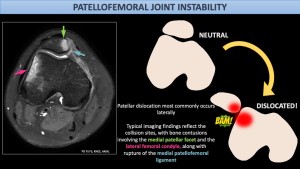

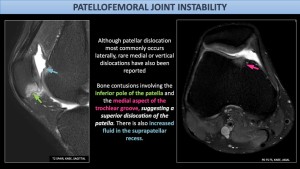

Typical imaging findings after lateral patellar dislocation include bone contusions and osteochondral injuries at the medial patellar facet and lateral femoral condyle, reflecting the collision sites between the patella and femur. Rupture of the MPFL is also one of the findings[2].

Predisposing factors include a shallow trochlear groove, increased sulcus angle, patella alta, increased TT–TG distance[2].

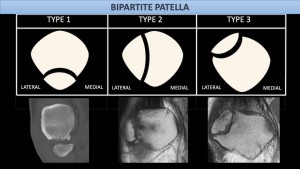

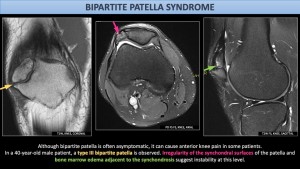

Bipartite and tripartite patella:The patella develops as cartilage and begins ossifying at 5–6 years from multiple centers that normally fuse. Failure of fusion results in accessory fragments separated by a fibrocartilaginous zone, termed bipartite (two fragments) or tripartite patella (three fragments)[1,5].

Although usually asymptomatic but may become painful after trauma or overuse due to disruption of the fibrocartilaginous interface, presenting with anterior knee pain, limited motion, and surrounding soft-tissue edema[5].

Nail-Patella Syndrome: Nail-Patella Syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder affecting the nails, skeleton, kidneys, and eyes. Patella may be small, dysplastic or absent. Due to abnormally shaped patella, recurrent subluxation and dislocation are common. Even without dislocation, the patella often appears more laterally and superiorly positioned than normal[6].

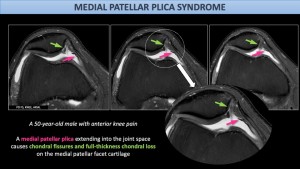

Medial plica syndrome: Plicae are synovial folds formed by incomplete resorption of embryonic septa of the knee joint [7].While suprapatellar and infrapatellar plicae are usually asymptomatic, the mediopatellar plica is less common but more likely to cause symptoms.Thickening or loss of elasticity of it may lead to anterior knee pain. When elongated it can cause chondral impingement and fissuring of the patellar cartilage, known as medial plica syndrome[4,7].

INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION

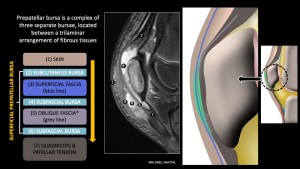

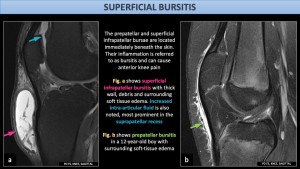

Superficial bursitis:The prepatellar and superficial infrapatellar bursae are the main superficial bursae of the anterior knee. The prepatellar bursa lies anterior to the patella and consists of three bursae between fibrous layers, while the superficial infrapatellar bursa is located anterior and slightly superior to the tibial tuberosity and is present in ~55% of specimens[4].

Superficial bursitis is a common cause of anterior knee pain, usually related to acute or repetitive trauma, and appears as fluid collection, synovitis and bursal wall thickening. It is classically termed housemaid’s knee due to prolonged kneeling. Non-mechanical causes include chronic glucocorticoid use, arthritis, infection[4].

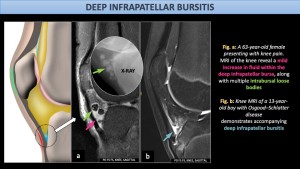

Deep infrapatellar bursitis: The deep infrapatellar bursa is a wedge-shaped structure located anteroinferior to the knee and does not communicate with the joint cavity.Bursitis presents with fluid accumulation and synovial inflammation, typically causing localized tenderness over the tibial tuberosity. It is classically associated with Osgood–Schlatter disease but may also occur with gout, infection, hemorrhage, or fat pad pathology[4].

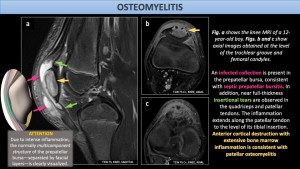

Osteomyelitis: Before ossification, the patella is mainly cartilaginous, and after ossification it has a rich blood supply; together with the absence of a physeal plate, these factors may contribute to its low incidence. Trauma may act as a predisposing factor.MRI may demonstrate bone marrow edema and inflammation, abscess formation, and joint effusion and synovitis. As the patella is covered by a thin cortical layer without a true periosteum, typical periosteal elevation seen in other bones may be absent in patellar osteomyelitis.[8]

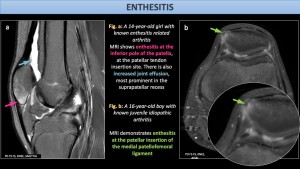

Enthesitis:Entheses are specialized anatomical units where tendons or fascia attach to bone.Enthesitis involving the patellar tendon insertion is most commonly seen at the inferior pole of the patella, particularly in juvenile inflammatory arthritis. Imaging may demonstrate bone marrow edema and adjacent soft-tissue inflammation such as deep infrapatellar bursitis[4,9].

Gout: Gout is caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in joints, soft tissues, and viscera. The knee joint may be involved. Depending on the sites of crystal deposition, gout can result in patellar erosions, patellar tendinopathy and bursitis[4].

TRAUMA AND OVERUSE INJURIES

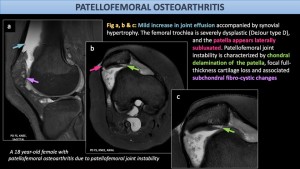

Patellofemoral osteoarthritis: The patella has thick posterior cartilage that enables it to withstand high mechanical loads. Although the patellofemoral joint is commonly involved in age-related osteoarthritis, it may also occur in younger individuals, most often due to patellofemoral joint instability. This leads to increased loading of the lateral patellar facet, where chondral damage is more frequent than in the medial facet. Cartilage degeneration correlates with increased T2 signal intensity, reflecting elevated water content and collagen disorganization[4].

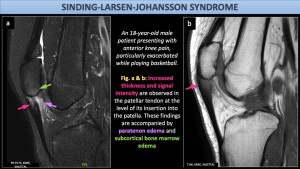

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Syndrome: This chronic traction apophysitis is caused by repetitive avulsion injury at the inferior pole of the patella in the immature skeleton, occurring at the patellar tendon insertion. It is most commonly seen in physically active adolescent boys and presents with pain and swelling at the inferior patella[4].

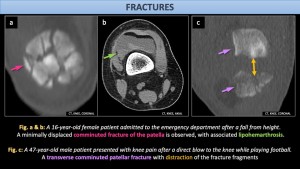

Fractures: The superficial anterior location of the patella makes it susceptible to trauma, including open injuries that may be complicated by osteomyelitis. Patellar fractures are classified as transverse (most common), vertical, comminuted, marginal, or osteochondral[4].

Sleeve avulsion fracture:Sleeve avulsion fractures occur in children aged 8–12 years and result from traumatic avulsion of the inferior pole of the patella due to forceful quadriceps contraction with the knee in flexion. This injury resembles Sinding-Larsen–Johansson syndrome but differs by its acute onset following trauma[4].

Patellar tendinosis and tears:The patellar tendon is prone to overuse and traumatic injury due to high mechanical demand. Histologically, the most common pathology is tendinosis, a non-inflammatory overuse condition characterized by collagen degeneration, typically involving the proximal posterior tendon, likely related to relative hypovascularity. Tendinosis predisposes the tendon to tearing[4].

Jumper’s knee occurs in athletes exposed to repetitive quadriceps contraction (e.g., basketball) and presents with anterior knee pain. Sinding–Larsen–Johansson syndrome predominantly involves the enthesis and is considered the juvenile equivalent of jumper’s knee [4].

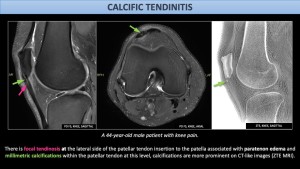

Calcific tendinitis:

Caused by metaplastic transformation of tenocytes into chondrocytes, resulting in calcium deposition within tendons. It may present with pain and limited range of motion. While common in the rotator cuff, patellar tendon involvement is rare and can be diagnostically challenging. Calcifications may be seen on radiographs or CT, while MRI typically demonstrates low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images. In some cases, imaging findings are subtle and diagnosis is made intraoperatively[10].

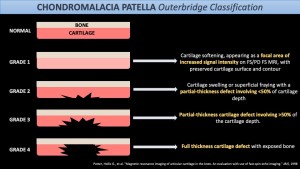

Chondromalacia patella:The posterior patellar surface is covered by hyaline cartilage. Trauma, overuse (runner’s knee), iatrogenic injections may lead to chondromalacia. Predisposing factors include patellofemoral instability, patella alta or baja, and lower limb malalignment. MRI is the modality of choice for cartilage assessment. Severity is commonly graded using the Outerbridge classification[11].

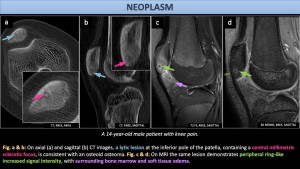

NEOPLASMS

Less than 1% of skeletal tumors occur in the patella. This sesamoid bone exhibits a tumor spectrum similar to that of an apophysis. Most patellar tumors are benign (75–90%), with giant cell tumor and chondroblastoma being the most common, followed by aneurysmal bone cyst, osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, and enchondroma. Malignant tumors are rare, typically occur in older patients, and are most often metastatic. Among primary malignant lesions, osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma and lymphoma are the most frequently reported[4,12].