Diagnosis and interventional radiology management

The diagnosis of ectopic varices requires a systematic approach in patients with liver disease or portal hypertension [3]. While endoscopy is the first-line tool for gastrointestinal bleeding, it has limitations in assessing ectopic varices. Therefore, contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Doppler ultrasound are crucial for diagnosis and intervention planning [1].

Contrast-enhanced CT provides key insights, especially when endoscopic treatment is not feasible due to the anatomical complexity; to make an accurate diagnosis when active small bowel bleeding is detected by capsule endoscopy; and in situations where endoscopy cannot be performed due to massive bleeding or in the absence of an endoscopist [1].

MRI, particularly magnetic resonance venography, is useful for younger patients, those needing repeated imaging, or those with hepatorenal syndromes [11]. Doppler ultrasound aids in initial screening and follow-up by assessing blood flow and portal vein patency [11].

In our cases, all patients underwent CT within 1–11 days before embolization. The detailed CT vascular mapping was able to identify pathology such as portal vein thrombosis and delineate afferent and efferent vessels.

After thorough imaging assessment, an appropriate endovascular intervention was planned.

For ectopic varices due to decompensated portal hypertension, the preferred initial treatment is transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) to decompress the portal system and reduce variceal bleeding. However, only selected patients benefit from it, requiring careful evaluation of contraindications to minimize the risks of adverse outcomes and patient mortality [7].

If TIPS is not feasible, additional variceal embolization should be considered. Retrograde transvenous obliteration (RTO) can be effective when the efferent vein connecting to systemic circulation is accessible. Antegrade transvenous obliteration (ATO) plays a crucial role as ectopic varices often have complex anatomy and frequently lack catheterizable efferences. Superficial portal veins, like recanalized umbilical veins, may offer a safe route for ATO [9].

Absolute contraindications for TIPS include advanced heart failure, tricuspid valve insufficiency, uncontrolled infections, biliary obstruction, and severe pulmonary hypertension [6]. Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) occurs in up to 90% of cases within three months post-TIPS, with 8% developing refractory HE, often linked to worsening liver disease [6, 7]. Although HE is not an absolute contraindication, careful risk assessment is necessary.

In our cases, TIPS was ruled out in all of the patients; two of them had severe tricuspid insufficiency with dilated right ventricle, one congestive heart failure and one portopulmonary hypertension; in two of them there was recurrent HE episodes and in another one the criteria were not met due to a low portosystemic gradient.

Given the vascular anatomy, ATO was the preferred approach in all patients, targeting the afferent vessel via transhepatic or transsplenic access.

The following section details each case according to anatomical location.

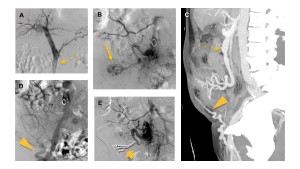

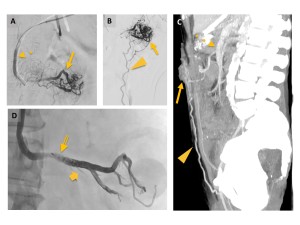

Rectal varices

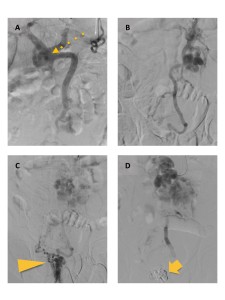

While the majority of lesions can be managed using endoscopic techniques, endovascular intervention is often required as a rescue approach. While afferent venous anatomy is relatively simple, efferent drainage is complex. Embolization of the isolated afferent vein, targeting the segment from the distal inferior mesenteric vein to the superior rectal vein via transhepatic or transsplenic access, is an effective treatment [1]. In our cases (Figures 3 and 4), the inferior mesenteric vein was the afferent branch, draining into the internal iliac veins. Both cases were treated with liquid embolic agent (EVOH), with one requiring a proximal vascular plug.

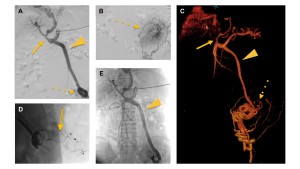

Duodenal varices

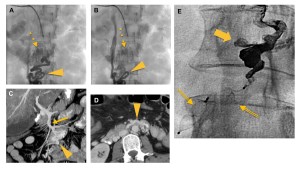

Endoscopic intervention is primary but may not ensure long-term hemostasis [8]. RTO is considered when retrograde access via the Retzius vein is feasible. However, the presente of complex and multiple mesocaval collaterals and hepatofugal flow changes during balloon occlusion often necessitate adjunctive treatments, including N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) injection, coil embolization, or simultaneous balloon occlusion. ATO is an alternative via collateral veins from the portal or superior mesenteric vein [1]. Endovascular treatment was performed in our case (Figure 6) after previous endoscopy which was ineffective. A portography revealed superior mesenteric vein-dependent varices with intraluminal bleeding in the duodenum. Selective embolization via superior mesenteric vein (ATO) was performed using two distal vascular plugs and liquid embolic agent (EVOH).

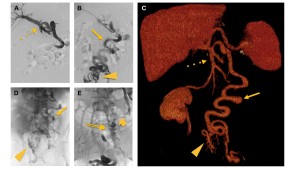

Stomal varices

They are easily identified due to the proximity of the bleeding site. When endoscopic treatment is not feasible, RTO or ATO are viable alternatives. The afferent vein is typically an isolated mesenteric vein supplying the bowel loop, facilitating endovascular treatment [1]. In the three cases (Figures 8, 9 and 10), the efferent venous plexus was complex and small-caliber, making retrograde access impossible. ATO was performed via transhepatic in one case and transsplenic in two. Portography identified the superior mesenteric vein as the afferent vein in two cases and the inferior mesenteric vein in one, with efferences draining into the cavo-iliac system via the external iliac vein. All cases were treated with liquid embolic agent (EVOH), combined with either proximal or distal vascular plugs.