ANATOMY

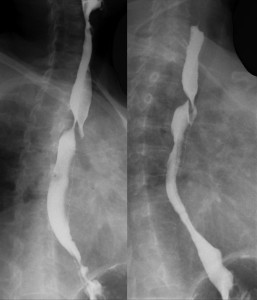

The esophagus is a tubular structure measuring 20–24 cm in length, extending from the pharynx to the stomach.

The structures detected in an esophageal study are:

- Upper esophageal sphincter: Represents the pharyngoesophageal junction and is formed by the cricopharyngeal muscle.

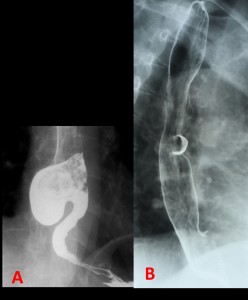

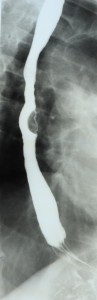

- Lower esophageal sphincter, phrenic ampulla, or esophageal vestibule: Located between the A and B rings. (Fig 3).

Fig 3: Impression of the cricopharyngeal muscle (yellow arrow), tubular esophagus (blue arrow), A-ring or tubulovestibular junction (green arrow), esophagogastric junction (red arrow), and V (esophageal vestibule).

Fig 3: Impression of the cricopharyngeal muscle (yellow arrow), tubular esophagus (blue arrow), A-ring or tubulovestibular junction (green arrow), esophagogastric junction (red arrow), and V (esophageal vestibule).

The barium esophagogram permits the visualization of the longitudinal, thin and uniform folds of the esophagus. Occasionally, transient transverse folds, primarily located in the middle and distal esophagus, are observed and referred to as "feline esophagus" (Fig 4).

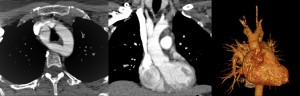

EXTRINSIC COMPRESSIONS

Mediastinal organs and structures can exert extrinsic compression on the esophagus, including:

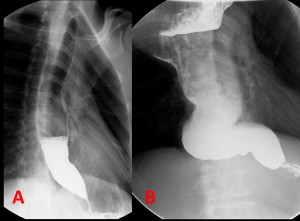

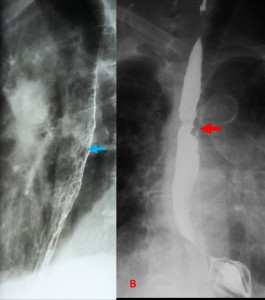

- The aortic arch, left main bronchus, and heart (Fig 5).

Fig 5: Esophageal compressions caused by the cricopharyngeal muscle (red arrow), aortic arch (yellow arrow), left main bronchus (green arrow), and heart (blue arrow).

Fig 5: Esophageal compressions caused by the cricopharyngeal muscle (red arrow), aortic arch (yellow arrow), left main bronchus (green arrow), and heart (blue arrow).

ESOPHAGEAL IMPRESSIONS

VASCULAR

- Aberrant right subclavian artery

It is the most common thoracic vascular anomaly. The right subclavian artery originates distal to the left subclavian artery, rather than from the brachiocephalic trunk.

It is often asymptomatic, but up to 10% of the patients can present dysphagia.

On a barium esophagogram it appears as an oblique impression on the posterior esophageal wall causing leftward displacement of the barium column and a characteristic "bayonet deformity" (Fig 6).

- Double aortic arch

It is the most common and severe “vascular ring” anomaly, characterized by the persistence of all four embryonic aortic arches on both sides, resulting in a double aortic arch.

Symptoms include dyspnea, feeding-associated cyanosis, stridor and dysphagia.

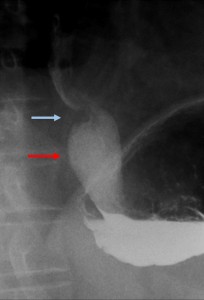

On the esophagogram, there is a characteristic indentation of the esophagus in an inverted “S” shape (Fig 7, 8).

- Ascending esophageal varices

Esophageal varices are dilated veins typically found in patients with severe liver disease.

On the esophagogram, they appear as serpentine, tortuous and longitudinal filling defects in the distal third of the esophagus, that change during inspiration on when performing the Valsalva maneuver (Fig 9)

INDENTATIONS

- Esophageal web

It is an indentation of the anterior face of the cervical esophagus, although it may occasionally encircle the esophagus. It can be congenital or acquired.

On a barium esophagogram it is seen as a filling defect, usually linear, on the anterior wall of the cervical esophagus (Fig 10).

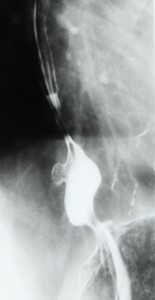

- Cricopharyngeal muscle achalasia

It is a esophageal motor disorder, and it is defined as a dysfunction of the cricopharyngeal muscle, where there is a lack of muscle relaxation during swallowing.

Findings on a barium esophagogram include contrast accumulation in a dilated pharynx with minimal passage into the esophagus, a cricopharyngeal bar, or intermittent posterior protrusion at the pharyngoesophageal junction (C5–C6) (Fig 11)

DIVERTICULA AND RINGS

PULSION DIVERTICULA

These are the most common type of diverticula, caused by an increase in intraluminal pressure that leads to the herniation of the mucosa and submucosa through the muscularis propria. Due to the absence of a muscular layer, they are considered pseudodiverticula.

Types:

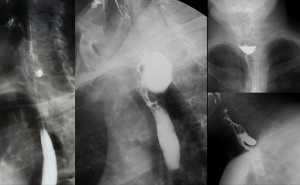

- Zenker’s Diverticulum

Also known as pharyngoesophageal diverticulum, it is a pharyngeal protuberance located in the midline of the posterior wall of the hypopharynx, just above the cricopharyngeal muscle at the C5-C6 level.

It is a pulsion pseudodiverticulum that results in the herniation of the mucosa and the submucosa through Killian’s triangle.

It is seen as a barium-filled sac located in the midline of the posterior wall of the distal pharynx, close to the pharyngoesophageal junction (Fig 12).

- Epiphrenic Diverticulum

It is a pulsion diverticulum located in the distal esophagus, above the lower esophageal sphincter and often on the right posterior wall. It is claimed to be a result of an increase in intraluminal pressure and associated with esophageal dysmotility (Fig 13).

- Midesophageal Diverticulum

Often multiple, variable in size, with smooth and rounded contours, these diverticula are associated with diffuse esophageal spams, appearing transiently (Fig 14).

- Pseudodiverticulosis

Pseudodiverticula represent dilated excretory ducts of the deep esophageal glands. It is rare benign condition, typically diagnosed in the 6th-7th decade of life.

On the barium esophagogram they are typically seen as numerous millimetric pouches with narrow necks, that often appear to “float” (Fig 15).

TRACTION DIVERTICULA

These are true diverticula presenting all the layers.

They are localized in the medial esophagus and in the barium esophagogram they typically lack a neck, which gives them a triangular or polygonal shape. These diverticula deplete of contrast after esophageal contractions (Fig 16).

ESOPHAGEAL MOTILITY DISORDERS

The barium esophagogram can diagnose some functional motility disorders, but final diagnosis should be based on manometry.

- Gastroesophageal reflux (Fig 17)

It is the most common esophageal disorder. Its cause has been proven to be the transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter for 10 to 60 seconds.

Esophagogram suggests the presence of reflux and of an associated hiatal hernia (Fig 17).

- Achalasia

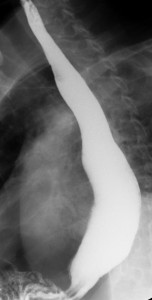

Achalasia is a primary esophageal motility disorder caused by the denervation of smooth muscle due to the destruction of Auerbach’s myenteric plexus.

On the barium esophagogram, the esophagus is dilated, with a "bird-beak" or “pencil-point” distal tapering narrowing, located just above the gastroesophageal junction. In very advanced cases, a sigmoid-shaped esophagus is seen (Fig 18).

- Diffuse esophageal spasm

It is a motility disorder characterized by multiple uncoordinated, intermittent contractions in the medial and distal esophagus, with a normal propagation wave but increased force and duration of contraction.

In the esophagogram, non-peristaltic contractions propelling the contrast medium in two directions can be seen, with sacculations and pseudodiverticula. Less than 5% of patients present a “corkscrew” or “rosary bead” pattern where normal peristalsis is interrupted by numerous tertiary contractions in the distal esophagus (Fig 19).

- Scleroderma

Up to 90% of patients with scleroderma may present gastrointestinal symptoms and esophageal involvement is the most common.

The barium esophagogram shows a dilation of the distal two-thirds of the esophagus, with dysmotility in the lower esophagus and difficulties in its depletion (Fig 20).

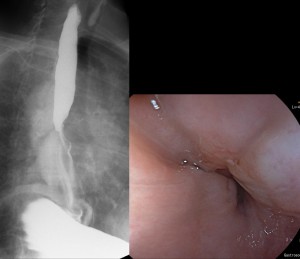

- POEM

Peroral endoscopic myotomy or POEM It is an endoscopic technique used in patients with achalasia or esophageal motor disorder.

An incision is made in the esophageal mucosa and subsequently a tunnel is created in the submucosa towards the lower esophageal sphincter and towards the cardia.

The esophagram shows "bulging" of the postmyotomy distal esophagus, as the esophagus protrudes through the myotomy (Fig 21).

STENOSIS

- Infectious esophagitis

Candida esophagitis is the most frequent cause of infectious esophagitis, often affecting immunocompromised patients, mainly AIDS patients, although it can also occur in severe motility disorders such as scleroderma or achalasia.

On the esophagogram, irregular plaque-like lesions separated by normal mucosa and small ulcers are seen (Fig 22).

- Caustic esophagitis

Ingestion of caustic substances can lead to liquefaction, necrosis, thrombosis, bacterial invasion and severe edema of the esophageal mucosa that can extend to the muscular layer.

The most severe late complication is esophageal stenosis, although permanent motility disorders may also develop (Fig 23).

- Benign esophageal tumors

Leiomyomas are the most frequent benign tumors of the esophagus, localized in the lower third of the esophagus at the intramural level (Fig 24).

- Malignant esophageal tumors

Esophagus cancer corresponds to less than 1% of all cancers and account for 4 to 10% of malignant gastrointestinal tumors.

Tumors located in the upper and middle esophagus correspond to squamous cell carcinomas, while those localized in the lower third are mainly adenocarcinomas. Patients present progressive dysphagia, that initially affects solids and progresses to liquids as the tumor grows and obstructs the esophageal lumen.

On the esophagogram, findings that suggest esophagus carcinoma are the presence of segmental stenosis with irregular borders (Fig 25).

The esophagogram can also detect complications, such as contrast extravasation into the mediastinum or esophagorespiratory fistulas to the trachea, bronchi or lungs (Fig 26, 27).