Lung surgery includes partial resection (wedge resection, segmentectomy, lobectomy) and complete pulmonary excision (pneumonectomy). In patients with low stage lung cancer (IA non-small cell lung carcinoma), non-anatomic (wedge) or anatomic (segmentectomy) resection of only a portion of the lung can be curative. In more advanced patients, the surgical protocol has to be established based on the location of the tumor and the involvement of the bronchial tree.

Chest radiographs are sufficient for early evaluation in patients with no clinical complains after surgery. Additional radiographs should be obtained after drain tube removal and before discharge. The scanning protocol for lung cancer is determined depending on the staging, with the first CT performed at 3 to 6 months postoperatively [3], followed by a CT every 6 months for up to three years. On these scans, the examiner should pay attention to signs early recurrence, as well as the possible long-term complications.

Normal postoperative findings:

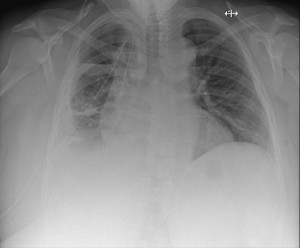

Normal postoperative findings may vary significantly between patients based on the patient’s functional status, type of resection, technique, concurrent diseases, etc. The examiner should assess the position of the pleural tubes: one in the upper lung area, to evacuate the pneumothorax, and the second usually in the dependent area, for the drainage of the fluid (Fig 1). It is important that all siphons remain within the pleural cavity; if any siphon is located in the chest wall, it may lead to extensive subcutaneous emphysema and increase the risk of infection.

After sublobar resections, the chest X-ray may appear normal or reveal a few areas of lamellar atelectasis. Depending on the suture materials used, small metallic clips might be visible in the resection area (see Fig. 2-3). A small pneumothorax can often be seen immediately after surgery and should resolve within a few days; however, if it persists, it may indicate an air leak potentially requiring reintervention.

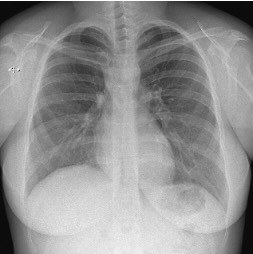

After a lobectomy or bilobectomy, typically on the right side, involving the upper and middle lobes, the resection site is clearly visible. Chest X-rays may reveal ipsilateral diaphragmatic elevation, decreased volume in one hemithorax, radiopaque clips near the hilum, pleural effusion, increased rib spacing, or even rib transection. Similar findings are observed on CT scans; in less conspicuous cases, the resected side may only display a reduced number of visible bronchi (Fig. 4).

After pneumonectomy, the affected hemithorax initially appears radiolucent due to the presence of air, but it gradually fills with fluid. By approximately three months post-surgery, the cavity is completely occupied by fluid, and the hemithorax shows volume loss with a shift of the ipsilalteral shift of the mediastinal structures and elevation of the hemidiaphragm. These changes are due to fibrosis and hyperinflation of the contralateral lung (see Fig. 5, 6).

Postoperative complications are classified as either early or late, and may involve injuries to the lung parenchyma, bronchial tree, pleura, or surrounding structures (see Fig. 7).

Early complications

Hemothorax may result from incorrect ligation of the bronchial vasculature or injury to a systemic vessel (such as the internal mammary or intercostal artery or vein). A frontal chest radiograph typically shows a dependent opacity in the affected hemithorax, but it cannot differentiate between pleural effusion, hemothorax, or chylothorax. Ultrasound can be useful for making this distinction by revealing the hematocrit sign, a key indicator of blood. CT imaging will display a hyperdense fluid collection and, in some cases, may even identify the source of the active bleeding (see Fig. 8).

Pneumothorax:

Improper ligation of the bronchi can lead to pneumothorax. Insufficient tension may cause suture failure, while excessive stress on the bronchial wall can result in necrosis and air leaks. This complication is more common in patients undergoing sleeve lobectomy or pneumonectomy. In pneumonectomy cases, an increase in the air component on the chest radiograph—indicating a reversal of the usual fluid filling pattern of the hemithorax—may be the first sign that reintervention is needed.

Lung Torsion:

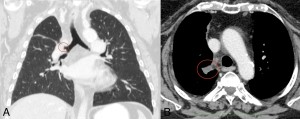

Lung torsion typically presents as a condensed lobe near the site of lobectomy, most commonly seen as the right middle lobe after a right upper lobectomy. Risk factors include incomplete fissures and persistent air or fluid collections. On frontal and lateral radiographs, lobar torsion appears as consolidated lobe in an abnormal position, although this finding is not specific. CT imaging can confirm torsion by showing a condensed, torsed lobe, a lack of opacification in the lobar artery distal to the occlusion, and signs of venous congestion.

Other Early Complications:

Additional issues include pulmonary edema (due to altered hydrostatic pressure), pneumonia (resulting from intraoperative contamination, aspiration, or mechanical ventilation), and adult respiratory distress syndrome (caused by disruption of the alveolocapillary barrier). These conditions have nonspecific imaging features and should be considered in any patient whose clinical status is worsening.

Late Complications

Empyema:

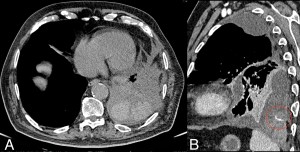

Empyema manifests as a loculated fluid collection with a thickened, enhancing pleura and may contain floating gas bubbles. This infection of the pleural space can develop several months to years after surgery (see Fig. 9). When the inflammatory process extends beyond the pleura, affecting the chest wall and adjacent soft tissues, it is referred to as empyema necessitans.

Postpneumonectomy syndrome (see Fig. 10) occurs when the mediastinum shifts to fill the space left by a large lung resection, causing the airways to be compressed between the mediastinum and the vertebral bodies. This is particularly common after left-sided resections, where the left main bronchus becomes trapped between the pulmonary artery and the aorta/vertebral column. The syndrome typically develops either as the mediastinum shifts or after significant fluid resorption within the cavity. Patients may experience dyspnea or recurrent infections. Treatment options include airway stenting or filling the pleural cavity with prosthetic material. Additionally, bronchial stenosis may occur following a sleeve lobectomy.