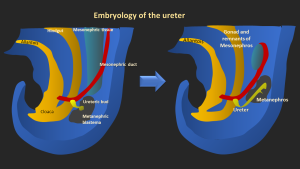

1.- Embryology of the Ureter

The ureter arises from the ureteric bud, an outgrowth of the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct that appears around the fourth week of gestation.

Abnormal development of the ureteric bud causes congenital ureteral anomalies, such as ureteral duplication, ectopic insertion, ureterocele, megaureter, and junctional obstructions. These issues arise from disrupted interaction with the metanephric blastema.

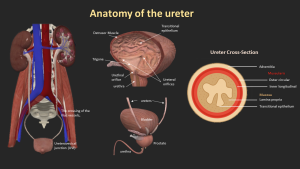

2. Anatomy of the Ureter

The ureters are paired muscular tubes, 3–4 mm in diameter, that transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder.

They begin at the ureteropelvic junction, descend retroperitoneally along the psoas major, cross the iliac vessels, and enter the bladder obliquely at the trigone.

Three physiological narrowings are identified: the UPJ, iliac vessel crossing, and ureterovesical junction, which are common sites for stone impaction.

The ureteral wall includes urothelium, lamina propria, muscular layers, and adventitia.

Peristalsis propels urine, and transient narrowing during peristalsis should not be confused with strictures.

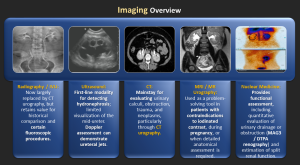

3. Imaging Overview

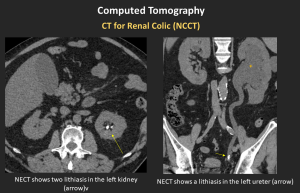

CT for Renal Colic (NCCT)

Gold standard for detecting stones

Low-dose protocols appropriate in non-obese patients

Secondary signs: ureteral wall edema, periureteral stranding, delayed nephrogram

CT Urography – Interpretation Checklist

- Lumen: filling defects

- Wall: thickening, abnormal enhancement

- Periureteral fat: stranding or masses

- Identify level and cause of obstruction

- Look for synchronous tumors in the collecting system

- Distinguish extrinsic compression from intrinsic disease

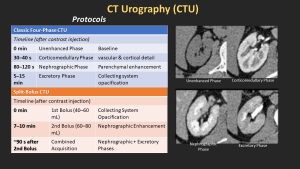

CT Urography protocol and Phases an

- Unenhanced

- Corticomedullary

- Nephrographic

- Excretory

Dual-Energy CT

- Differentiates uric acid vs non–uric acid stones → guides medical vs surgical management.

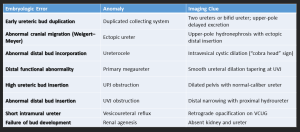

4. Anatomical Variants & Congenital Pathology

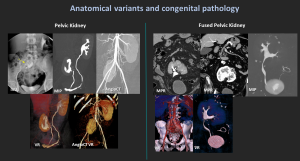

4.1 Pelvic Kidney / Fused Pelvic Kidney

Congenital anomaly with failed renal ascent; kidney remains in the pelvis.

May appear fused (“cake kidney”).

Short ureters, possible malrotation.

Differential: crossed-fused ectopia, horseshoe kidney.

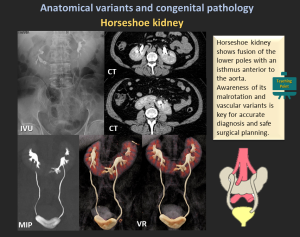

4.2 Horseshoe Kidney

- Most common fusion anomaly (1:400–600).

- Fusion of lower poles with an isthmus anterior to the aorta.

- Associated findings: malrotation, aberrant vessels, obstruction, infection, stones.

- Imaging: US (low midline kidney), CT/MRI defines isthmus & vasculature.

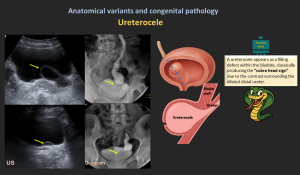

4.3 Ureterocele

- Cystic dilation of the distal ureter within bladder wall resulting from congenital obstruction at the ureteral orifice.

- “cobra-head sign” on IVU.

- Classification

- Intravesical (simple) ureterocele: Entirely confined within the bladder

- Ectopic ureterocele: Extends into the bladder neck or urethra

- Symptoms: UTIs, obstruction, stones.

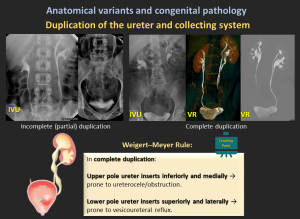

4.4 Duplication of the Ureter and Collecting System

- Ureteral duplication is a common congenital anomaly where two ureters drain a single kidney, occurring in approximately 1 in 160 live births.

- It can be incomplete (single ureter before the bladder) or complete (two separate ureters).

- It results from ureteric bud duplication and may cause hydronephrosis, reflux, UTIs, obstruction, or incontinence, particularly in females with an ectopic ureter.

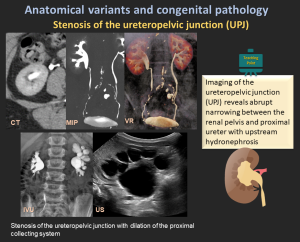

4.5 Ureteropelvic Junction (UPJ) Obstruction

- The most common cause of upper urinary tract obstruction, particularly in children.

- Etiology: Congenital (abnormal muscle development, high insertion, crossing vessels) or acquired (fibrosis, postsurgical changes).

- Imaging: Hydronephrosis with abrupt UPJ narrowing, best assessed by ultrasound, CT/MR urography, and diuretic renography.

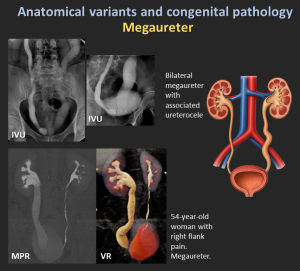

4.6 Megaureter

Megaureter refers to abnormal dilatation of the ureter, with or without associated dilatation of the upper collecting system.

- Primary obstructive megaureter: Functional distal obstruction due to a short aperistaltic segment, producing a characteristic tapered “beak-like” distal ureter.

- Refluxing primary megaureter: Caused by vesicoureteral junction incompetence with urine reflux.

- Non-obstructive, non-refluxing primary megaureter: Most common neonatal form; ureteral dilatation without obstruction or reflux.

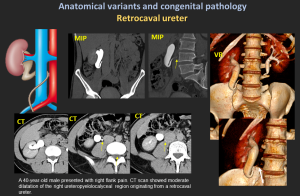

4.7 Retrocaval (Circumcaval) Ureter

- Ureter passes posterior to the IVC due to abnormal IVC development.

- “Reverse-J” appearance; right-sided hydronephrosis.

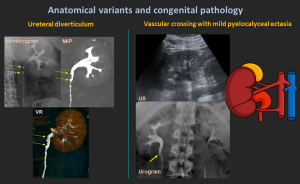

4.8 Ureteral Diverticulum

Congenital or acquired; communicates with the ureter through a narrow neck.

4.9 Vascular Crossing

Accessory renal vessels may compress the UPJ leading to obstruction.

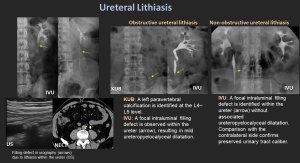

5. Ureteral Lithiasis

- Ureteral stones most commonly lodge at physiologic narrowings (UPJ, iliac vessel crossing, UVJ) and typically present with renal colic.

- Most frequent cause of ureteral filling defects

- Predominantly affects adults aged 30–60 years (≈12% of men, 5% of women)

- Calcium oxalate is the most common composition

- Most calculi show CT attenuation >200 HU; indinavir stones are an exception, demonstrating soft-tissue density

- NCCT: gold standard for detection and localization.

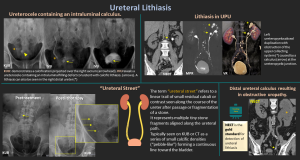

- Non-obstructive vs obstructive stones

- Obstructive stones: hydronephrosis, delayed excretion, wall edema.

- “Ureteral Street”: Linear trail of tiny lithiasis fragments along the ureter after passage or lithotripsy.

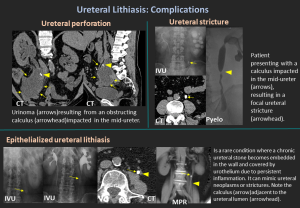

Complications

- Hydronephrosis

- Infection / pyelonephritis

- Ureteral stricture

- Perforation

- Urinoma

- Epithelialized Ureteral Stone: Rare: calculus becomes embedded in urothelium, mimics tumor or stricture.

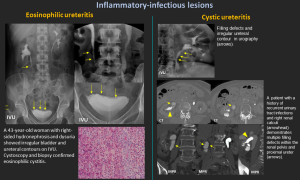

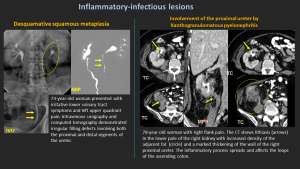

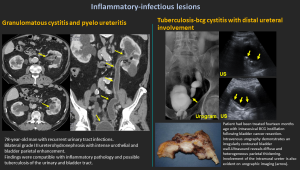

6. Inflammatory-Infectious Lesions

Inflammatory-infectious lesions usually appear as diffuse wall thickening of ureters.

6.1 Eosinophilic Ureteritis

- Rare inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration.

- Causes narrowing & hydronephrosis; associated with eosinophilic cystitis.

- Diagnosis: histology; treatment with corticosteroids or surgery.

6.2 Cystic Ureteritis

- Multiple small submucosal cysts → smooth mural filling defects.

- Often linked to chronic infection or lithiasis.

6.3 Desquamative Squamous Metaplasia

- Mimics nephrolithiasis or malignancy.

- Patients may pass keratinized flakes.

- Treatment usually conservative.

6.4 Xanthogranulomatous Pyelonephritis (XGP)

- Rare chronic granulomatous infection; often with obstructing calculus.

- May extend to ureter.

6.5 Granulomatous Cystitis / Ureteritis

- Seen in chronic infections, including tuberculosis.

6.6 BCG-Related Ureteritis

- After intravesical BCG therapy; causes irregular bladder wall and intramural ureter involvement.

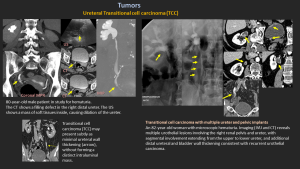

7. Tumors

7.1 Transitional Cell Carcinoma (TCC)

- Most common ureteral malignancy.

- Distal ureter most affected (73%).

- Types: papillary (80–85%, often multifocal) and non-papillary.

- Imaging: circumferential thickening, filling defects, abnormal enhancement.

- Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) may present subtly as minimal ureteral wall thickening (arrow), without forming a distinct intraluminal mass.

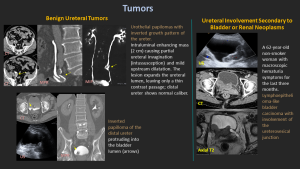

7.2 Benign Ureteral Tumors

Urothelial papillomas, fibroepithelial polyps

Appear as solitary pedunculated enhancing intraluminal masses.

7.3 Secondary Involvement

Spread from bladder carcinoma or renal pelvis tumors.

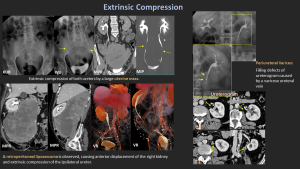

8. Extrinsic Compression

Main Causes

- Pelvic or retroperitoneal tumors (cervix, colon, ovary, prostate)

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis

- Vascular anomalies

- Postsurgical scars

- Pregnancy

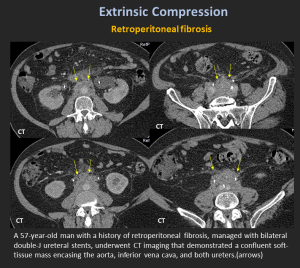

Retroperitoneal Fibrosis

A rare condition characterized by dense fibrous tissue around the abdominal aorta and iliac vessels, often encasing the ureters and inferior vena cava.

Etiology: Primarily idiopathic (Ormond's disease, autoimmune/IgG4-related, ~70%) or secondary to malignancy, infection, drugs, surgery, trauma, or radiation.

Imaging:

- CT: Plaque-like, isoattenuating soft tissue around the aorta/ureters.

- MRI: T2 hyperintense in active stages, T2 hypointense when chronic.

- FDG-PET/CT: Identifies active inflammation and helps exclude malignancy.

Other causes

Periureteral Varices: Rare cause of hematuria; give a “beaded” appearance on IVU.

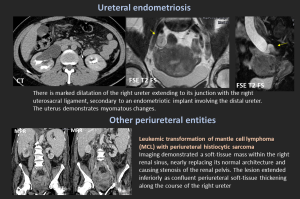

Ureteral Endometriosis: <1% of all endometriosis; intrinsic or extrinsic. Can cause silent loss of renal function.

Lymphoma / Histiocytic Sarcoma: May encase ureter and renal pelvis.

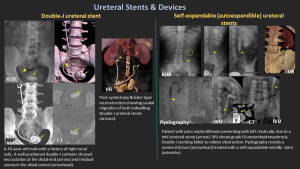

9. Ureteral Stents & Devices

9.1 Double-J Stent

- Radiopaque tube with curled ends in renal pelvis & bladder.

- Maintains patency; used for obstruction (stones, strictures, tumors).

- Complications: migration, encrustation, infection, discomfort.

9.2 Self-Expandable Metallic Stents

- Nitinol-based; used for malignant or refractory benign obstruction.

- Risks: tumor ingrowth (uncovered), encrustation, injury, removal difficulty.

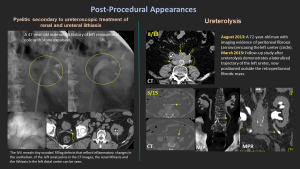

10.- Post-Procedure Imaging:

10.1 After URS/Laser Lithotripsy:

Ureteral edema, small residual fragments, and transient wall hyperenhancement are common findings.

Following Tumor Therapy (Ablation/Resection):Mural irregularity; potential strictures should be monitored.

10.2 Ureterolysis

Definition: Surgical dissection to release the ureter from scar tissue or fibrosis.

Purpose: Restores ureteral patency and prevents hydronephrosis due to extrinsic obstruction.

Indications: Retroperitoneal fibrosis, post-surgical adhesions, endometriosis, tumoral compression, and inflammatory fibrosis.

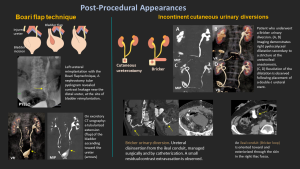

10.3 Boari Flap Technique:

A reconstructive technique for distal/mid-ureteral defects where direct reimplantation isn’t possible. A bladder wall flap is used to bridge the gap and restore urinary continuity.

10.4 Incontinent Cutaneous Urinary Diversions:

Cutaneous Ureterostomy: Direct ureteral connection to the abdominal wall, used when bowel segments can't be utilized (e.g., in inflammatory bowel disease).

Ileal Conduit (Bricker): A 20 cm ileal segment is used to connect both ureters, with the distal end forming a stoma on the skin.

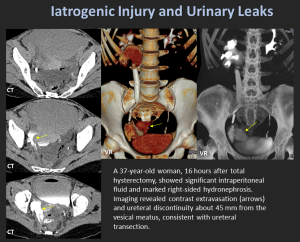

11. Iatrogenic Injury & Urinary Leaks

High-Risk Procedures

- Hysterectomy

- Colorectal surgery

- Pelvic oncologic surgery

Mechanisms

- Transection

- Ligation

- Devascularization

- Thermal injury

Imaging Findings

- Contrast extravasation

- Urinoma

- Non-opacified distal ureter

- Acute hydronephrosis

Early recognition is crucial to preserve renal function.