Pulmonary amyloidosis presents with different radiologic patterns, including nodular parenchymal, diffuse alveolar-septal, cystic, and tracheobronchial forms.

I-Pulmonary amyloidosis:

Pulmonary amyloidosis is more often a localized process rather than part of a systemic disease. It manifests in two distinct radiologic patterns: nodular and alveolar septal pulmonary amyloidosis. However, imaging findings are often nonspecific, requiring further evaluation for definitive diagnosis.

a. Nodular Involvement:

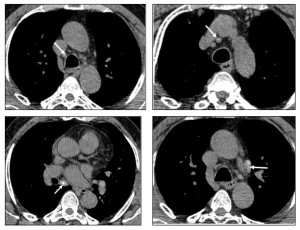

The typical presentation is observed in an asymptomatic adult, most commonly in the sixth decade of life, with incidental abnormalities detected on a chest radiograph.

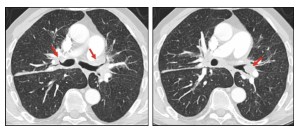

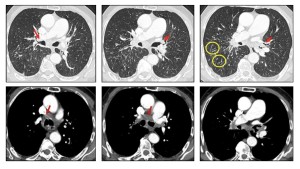

- On CT, nodular amyloidosis (NA) appears as solitary or multiple pulmonary nodules and can mimic various diseases, including granulomatous infections and malignancy.

- NA is commonly associated with localized forms of amyloidosis.

Solitary tumor-like deposits, referred to as amyloidomas in the absence of systemic disease, are identified in approximately 60% of cases. Multiple pulmonary nodules are frequently observed, predominantly in the upper lobes, with the following characteristics:

- Smooth, lobulated, or spiculated margins may raise suspicion for malignancy.

- Central or punctate calcifications are sometimes present.

- Rare cavitation

Over time, these nodules can grow and evolve into larger masses, reaching sizes up to 15 cm.

Consolidation within the lung parenchyma may also be seen, which can suggest other conditions, such as infection or inflammation.

Due to the variable imaging presentation, a definitive diagnosis based on imaging alone is challenging. While a detailed clinical assessment may raise suspicion, histopathological confirmation via biopsy is often necessary, with most deposits consisting of AL amyloid.

The natural course of nodular parenchymal amyloidosis is generally indolent, with lesions slowly increasing in size and number. Despite this, the overall prognosis remains excellent, and treatment is rarely required.

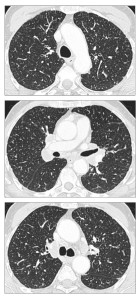

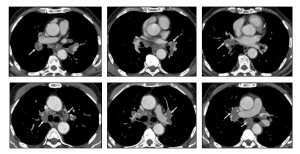

b. Alveolar septal pulmonary amyloidosis:

Alveolar septal pulmonary amyloidosis, although less common, is often more clinically significant than the nodular parenchymal form. Patients with this type are more frequently symptomatic and have a higher risk of progressing to pulmonary hypertension and respiratory failure. Diffuse alveolar septal amyloidosis (DASA) is rare and is more common in the subtype with systemic amyloidosis. CT chest findings in pulmonary amyloidosis are diverse and include:

- Reticulation.

- Thickening of interlobular septa.

- Peribronchovascular interstitial thickening.

- Micronodules can present with lymphatic, random, or centrilobular distribution.

- Ground-glass opacities.

- Consolidation.

Micronodules may be perilymphatic, resembling patterns seen in carcinomatous. Lymphangitis.

Less commonly, cystic changes, calcifications, and basal emphysematous changes are present, the latter due to alveolar wall damage.

The differential diagnosis based on imaging includes:

- Silicosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Carcinomatous lymphangitis

- Interstitial lung diseases, especially when reticulation is the primary finding on CT.

II- Tracheobronchial amyloidosis:

Tracheobronchial amyloidosis (TBA) is primarily characterized by focal, multifocal, or diffuse submucosal amyloid deposits affecting the trachea and main bronchi, with rare involvement of the segmental bronchi. While it is more commonly isolated, airway involvement may also be observed in systemic amyloidosis but is less frequent. TBA is more common in men (1.6:1) during the fifth and sixth decades of life, and it most often presents as localized ALamyloidosis, with less frequent association with systemic amyloidosis. The disease typically follows an indolent course with no known progression to systemic amyloidosis.

Airway involvement, including the trachea, usually presents with submucosal plaques but can occasionally manifest as solitary deposits that mimic an endobronchial neoplasm. Symptoms commonly include dyspnea, cough, wheezing, hemoptysis, and recurrent pneumonia.

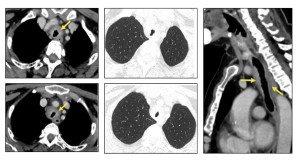

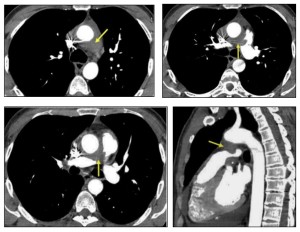

Imaging findings on CT typically include:

- Nodular thickening of the tracheal wall (60%)

- Calcifications (53%)

- Airway obstruction (47%)

The affected airway wall may demonstrate high attenuation due to calcification or ossification. If high-attenuation thickening of the airway wall is detected, along with long-segment narrowing of the lumen, amyloidosis should strongly be suspected.

Three patterns of airway involvement have been described:

- Proximal (upper tracheal involvement), often presenting with upper airway symptoms.

- Mid or distal (tracheal and main bronchial involvement), leading to lower airway symptoms, lobar collapse, or recurrent pneumonia.

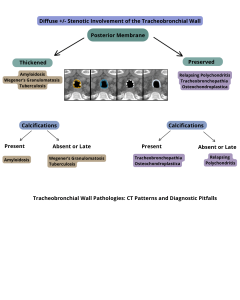

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Granulomatous diseases (such as tuberculosis or sarcoidosis)

- Tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica

- Relapsing polychondritis

Key differentiating features from other conditions include the involvement of the tracheal posterior membrane in tracheobronchopathia osteochondroplastica (TBA), a finding not seen in cartilage disorders, such as relapsing polychondritis.

Therefore, when imaging shows:

- High-attenuation thickening of the airway

- Long-segment narrowing

A diagnosis of amyloidosis should be strongly considered.

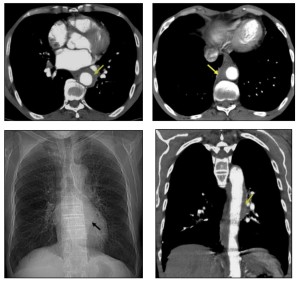

III- Mediastinal Amyloidosis:

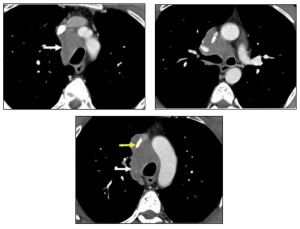

Mediastinal involvement is most frequently observed in systemic amyloidosis and can present as:

- Multistation lymphadenopathy or localized involvement in specific anatomical regions.

- Isolated tumefactive lesions (amyloidomas) can occur in any mediastinal compartment.

- Perivascular thickening.

Symptoms depend on the lesion’s location and its proximity to adjacent structures. Mediastinal disease often presents as asymptomatic lymphadenopathy, which is the third most common thoracic manifestation of amyloidosis, following airway and nodular parenchymal disease.

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy may display punctate, diffuse, or eggshell calcification.

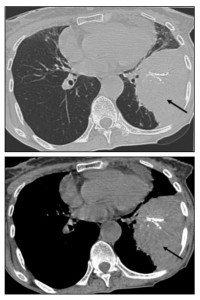

IV- Pleural effusion in amyloidosis:

A-Prevalence and types:

- Pleural effusions occur in ~20% of AL amyloidosis cases.

- One-third of these effusions are large and resistant to diuretics.

- Rare in AA and ATTR amyloidosis.

B-Imaging Considerations:

- Effusions may be unilateral or bilateral, transudative or exudative.

- Persistent pleural effusions (PPEs) should raise suspicion for direct pleural amyloid deposition, especially when cardiac and renal dysfunction are absent.

C-Diagnosticc and Prognostic Implications:

- CT and ultrasound can help assess effusion characteristics.

- Pleural biopsy may confirm amyloid infiltration.

- PPEs in AL amyloidosis are linked to poor prognosis if untreated.