Scrotal US can directly demonstrate testicular and peri-testicular abnormalities, as well as secondary changes caused by distal genital duct obstruction, meaning it may identify a big part of male infertility causes, per se.

This technique is performed with a high-frequency linear-array transducer, with the patient in a supine position. Color flow Doppler US of testicular and spermatic cord vascularity is routinely performed.

Obstructive causes

Obstruction can occur anywhere along the ductal system, so US is a useful tool that helps determine the level of obstruction and plan treatment, as distal tract obstructions can be treated under sonographic guidance, while epididymal or vas obstruction usually undergo microsurgery.

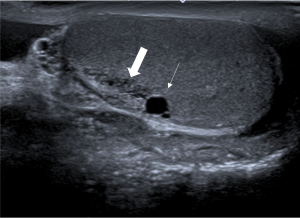

In these cases, scrotal US is essentially a preliminary test for detecting secondary signs of obstruction, as retention of secretions leads to macroscopic changes proximal to the site of obstruction – namely, ectasia of rete testis (Figure 1), dilation of epididymal ductules, and intratesticular cysts (Figure 1).

For more specific findings, transrectal US (TRUS) is the modality of choice, as it enables high-resolution imaging of the distal genital tract.

1. Epididymal obstruction

- Post-infection: epididymitis can lead to scarring and subsequent obstruction, which, sonographically, appears as a bulky epididymis with heterogeneous echotexture and/or epididymal calcifications (Figure 2). Acute gonorrhea and sub-acute chlamydial or granulomatous infections like tuberculosis are important causes, particularly in developing countries.

- Post-surgical: iatrogenic epididymal obstruction may occur after removal of epididymal cysts.

- Idiopathic epididymal obstruction

2. Vas Deferens obstruction

- Congenital absence of vas deference (CAVD): considered the most common congenital abnormality causing obstructive azoospermia [5], characterized by an abrupt termination of the epididymal tail into a rudimentary echogenic cord-like structure; absence of the ampulla of the vas deferens and abnormalities of the seminal vesicle and ejaculatory duct can be detected on TRUS [6-7]. Up to 82% of patients with CBAVD have at least one mutation within the cystic fibrosis gene, so these patients must be considered for screening and genetic counseling before fertility treatments [8].

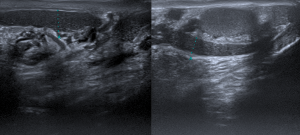

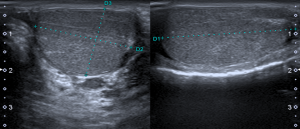

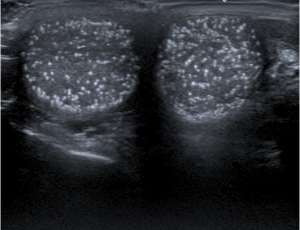

- Post-vasectomy: described as the most common cause of vasal obstruction; US shows bilaterally bulky epididymis with a finely speckled appearance (Figure 3).

3. Ejaculatory duct (ED) obstruction

- Calculi: mainly located at the level of the ampulla; TRUS reveals echogenic foci with distal shadowing along the course of ED, and dilatation of the proximal duct.

- Prostatic lesions: prostatic utricles and Mullerian cysts may cause infertility by ED compression, as well as prostatic abscesses.

- ED cysts

- Post-surgical (bladder neck surgery)

Non-obstructive causes

NOC of infertility are linked to an alteration in sperm production or function. They can be divided into pre-testicular, testicular, and post-testicular causes. As illustrated in Table 1, testicular causes are the ones that can be easily assessed and diagnosed by scrotal US, namely varicoceles, primary testicular tumors, and testicular abnormalities, such as cryptorchidism, testicular atrophy, and orchitis and epididymo-orchitis.

Although not always correctable, these conditions play an important role in male infertility, and their recognition should be encouraged so that treatment and quality of life can be sought.

1. Varicocele

Varicoceles are abnormal dilatations of the pampiniform plexus, secondary to retrograde flow via the spermatic vein due to incompetent or absent valves. They are the most common correctable and non-obstructive cause of male infertility, being identified in 40% of males with primary infertility and 81% of males with secondary infertility [9].

The precise correlation between varicoceles and infertility is still not clear, and many theories have been created. It is now thought that the pathophysiology behind this connection is either poor venous drainage that disrupts the countercurrent heat exchange in the spermatic cord or increased testicular perfusion, causing increased scrotal temperature and subsequently impaired spermatogenesis [10].

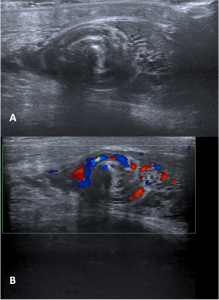

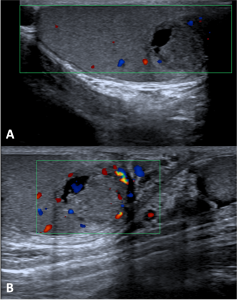

The diagnosis should be made clinically, while gray-scale US combined with color duplex US can confirm it by demonstrating a reflux of blood and an increase in the venous diameter to at least 3 mm during the Valsalva maneuver (Figure 4).

2. Primary testicular tumors

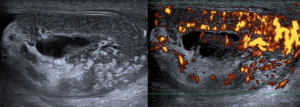

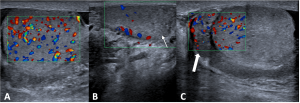

Testicular cancer is the leading cancer in young males aged 15–34 years, particularly germ cell tumors, which have been linked to decreased semen quality and fertility problems [11]. Concurrently, it is widely accepted that infertile males have an increased risk of testicular cancer, even after excluding the common risk factors for testicular cancer and infertility [12]. Although the features of testicular malignancy are diverse, most appear heterogeneous and hypoechogenic compared with the surrounding parenchyma, usually with increased vascularity within the lesion (Figure 5).

3. Testicular abnormalities

- Cryptorchidism: refers to the absence of one or both testis in the scrotal sac, normally due to a failure of descent into the cooler environment of the scrotal sac, which impairs spermatogenesis and predisposes to infertility and malignancy. Even after orchidopexy, men may be sub-fertile [13]. An undescended testis appears as a homogeneously hypo-echoic ovoid structure with reduced volume and vascularity, most commonly in the inguinal canal (Figure 6).

- Testicular atrophy: on sonography, it appears as a global reduction in the volume of the affected testis, which has an altered testicular echotexture and high resistive index of intra-testicular vessels (Figure 7). It is associated with reduced spermatogenesis and fertility, and its causes vary from inflammation to trauma and endocrinopathies [14].

- Orchitis and epididymo-orchitis: although there is still a lack of conclusive epidemiological data, infections/inflammations of the genital tract are considered the most frequent causes of male infertility [15], as chronic inflammatory conditions adversely affect spermatogenesis and irreversibly alter both the number and quality of sperm. US shows testicular enlargement and heterogeneity of echotexture with an enlarged hypo/hyperechoic epididymis and increased blood flow to both testis and epididymis on color Doppler US (Figure 8) – the epididymis is spared in pure orchitis.

Other causes

1. Testicular Microlithiasis: caused by calcium deposits within the seminiferous tubules [16]; defined, sonographically, as five or more echogenic foci without posterior acoustic shadowing smaller than 3 mm (Figure 9). Although its link with infertility is unclear, it may be related to the degeneration of cells lining the seminiferous tubules [17].

2. Testicular torsion: defined as the twisting of the spermatic cord with progressive impairment of venous drainage and ultimately arterial ischemia. If left untreated, this may progress to testicular infarction and male infertility, which makes detorsion within 4–6 hours of the acute onset imperative. Gray-scale US is useful in identifying the twisted cord and its direction, allowing a successful manual detorsion of the testis.