Placental Anatomy and Normal Implantation

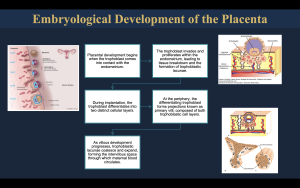

The placenta is a complex, transient organ essential for fetal development, originating from the differentiation of the blastocyst into the trophoblast and inner cell mass. By the end of the first trimester, the definitive placental disc is formed, characterized by approximately 15–20 functional units known as cotyledons. Anatomically, it consists of the fetal surface (chorionic plate) and the maternal surface (decidua basalis).

The placental–uterine interface is a critical functional zone where the decidua separates the placental villi from the underlying myometrium. A key histological feature in normal pregnancies is the Nitabuch layer, a fibrinoid deposit that acts as a biological boundary, preventing excessive trophoblastic invasion into the uterine wall

Pathophysiology of Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS)

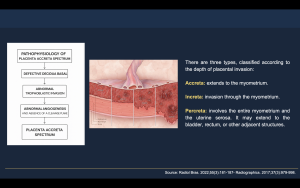

Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS) refers to a range of disorders characterized by abnormal placental adherence to the myometrium. The primary pathogenic mechanism involves a defective or absent decidua basalis, most commonly related to prior uterine trauma. In the absence of the Nitabuch layer, trophoblastic tissue invades the myometrium directly (Figure 1).

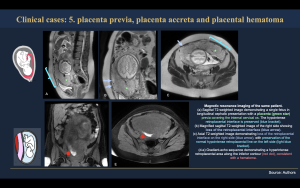

PAS is classified according to the depth of placental invasion (Figure 2-3):

- Placenta accreta: Chorionic villi attach directly to the myometrium without invasion.

- Placenta increta: Chorionic villi invade deeply into the myometrium.

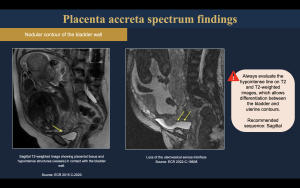

- Placenta percreta: Chorionic villi penetrate through the entire myometrium and may extend into adjacent pelvic organs, most commonly the urinary bladder.

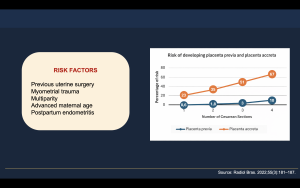

The most significant risk factors include a history of cesarean delivery and the presence of placenta previa, with the risk increasing exponentially with each subsequent uterine surgery.

Clinical Presentation and Obstetric Impact

Clinically, PAS is often asymptomatic during pregnancy but manifests dramatically at delivery due to failure of placental separation, resulting in life-threatening postpartum hemorrhage. It represents a leading cause of emergency peripartum hysterectomy and severe maternal morbidity.

Therefore, establishing an effective bridge between clinical suspicion and diagnostic imaging is essential. Accurate prenatal diagnosis, particularly with MRI, enables appropriate multidisciplinary surgical planning, which has been shown to significantly reduce maternal complications and improve obstetric outcomes.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Protocol for Placenta Accreta Spectrum

Clinical Role and Indications

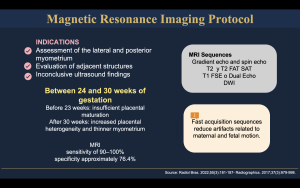

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful adjunct to ultrasound in the evaluation of suspected placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) disorders. While transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound remain the first-line imaging modalities, MRI is indicated when:

- Ultrasound findings are inconclusive, especially in posterior placental locations.

- There is difficulty assessing the depth of placental invasion or extrauterine extension.

- Surgical planning requires detailed evaluation of the placenta-myometrium and placenta-adjacent structures.

The use of MRI in PAS has notably increased over the past decade as clinical demand for precise preoperative assessment and multidisciplinary planning has grown.

Optimal Timing

The ideal gestational window for placental MRI is between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation. Before 24 weeks, diagnostic sensitivity is lower due to less pronounced imaging features, and after 32–34 weeks, physiologic changes such as myometrial thinning can reduce image clarity.

Patient Preparation

- MRI should be performed on 1.5-T or 3.0-T scanners to optimize spatial resolution and signal.

- The patient lies supine with a moderately full bladder, which improves visualization of the lower uterine segment and cervix, particularly in suspected percreta.

- Breath-holding techniques are used when possible to reduce motion artifacts.

- Gadolinium-based contrast agents are generally avoided in pregnancy due to potential fetal risks, though some centers may use them selectively when additional specificity is warranted.

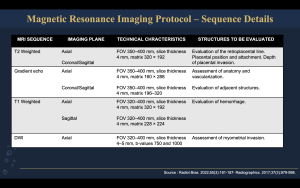

Core MRI Sequences

A standardized MRI protocol employs a combination of fast, motion-resistant sequences optimized to assess placental morphology, invasion, and anatomy:

- T2-Weighted Imaging (T2WI)

- Multiplanar (axial, sagittal, coronal) T2WI is the backbone of the examination, providing delineation of placental margins, myometrium-placental interface, and depth of invasion.

- Fast spin-echo sequences such as SSFSE/HASTE are preferred to minimize motion.

- Balanced steady-state free precession (TrueFISP/FIESTA/bFFE)

- Useful for rapid morphological assessment with high contrast between placenta, amniotic fluid, and myometrium.

- Enhances identification of vascular features and placental contour.

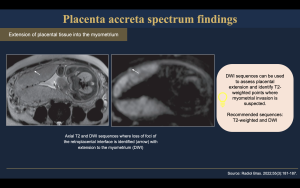

- Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI)

- Ancillary sequence to evaluate placental tissue microstructure and help delineate the interface between placenta and myometrium.

- Particularly helpful when conventional imaging is equivocal.

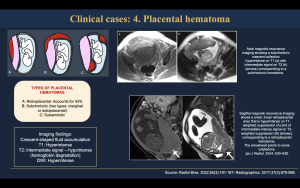

- (optional) T1-Weighted Imaging with Fat Saturation

- Assesses hemorrhage within or adjacent to the placenta.

- Can be included based on clinical indication, though it is not universally essential.

Typical total scan time is approximately 25–35 minutes, with a radiologist present to adjust planes dynamically if needed for better visualization of suspected invasion planes. MRI parameters should be optimized for fast acquisition and motion resistance. Balanced steady-state free precession and single-shot T2-weighted sequences with appropriate flip angles and slice thickness are essential to accurately assess placental invasion (Figure 4-5).

Placental Assessment: A Compartment-Based Approach

A systematic, compartment-based evaluation improves diagnostic accuracy in PAS and facilitates structured interpretation on MRI. Assessment should include the placenta itself, the uteroplacental interface and myometrium, and extrauterine structures

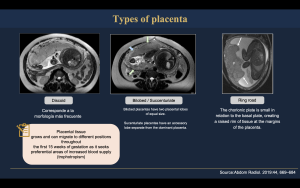

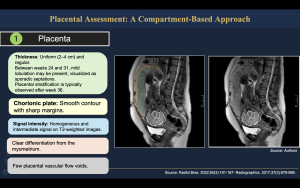

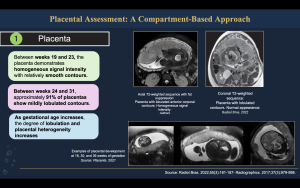

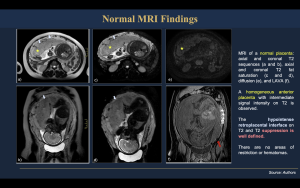

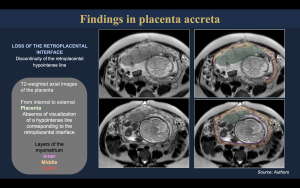

Normal MRI Findings

- Placenta (Figure 6-8).

- Homogeneous placental signal intensity on T2-weighted images

- Smooth placental contour

- Well-defined placental margins

- Absence of focal bulging or lobulation

- Normal placental thickness for gestational age

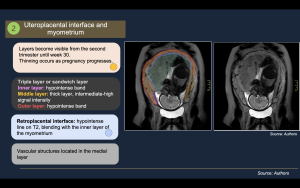

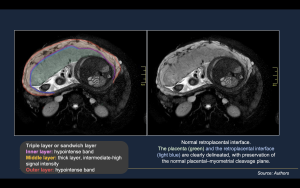

- Uteroplacental Interface and Myometrium (Figure 9-10).

- Continuous, hypointense retroplacental line on T2-weighted images

- Preserved decidua basalis and normal placental–myometrial interface

- Uniform myometrial thickness beneath the placenta

- Clear cleavage plane between placenta and myometrium

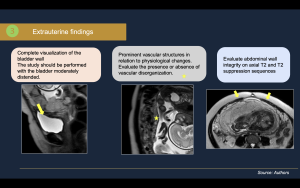

- Extrauterine Findings (Figure11).

- Preserved uterine serosal contour

- Normal appearance of adjacent pelvic organs

- Absence of abnormal vascular structures

- Clear fat planes between uterus and surrounding structures

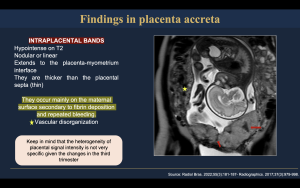

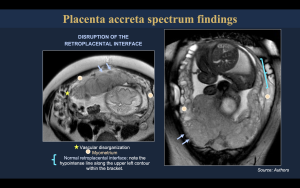

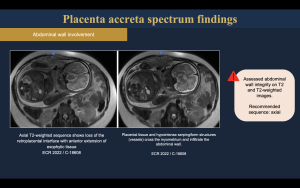

Magnetic resonance imaging findings of placenta accreta spectrum can be systematically assessed using a compartment-based approach. At the placental level, abnormal findings include marked placental heterogeneity, intraplacental T2 hypointense bands, irregular or lobulated placental contours, focal uterine bulging, and disorganized vascular architecture. At the uteroplacental interface and myometrium, characteristic features include thinning or complete loss of the normal hypointense retroplacental line, focal or diffuse myometrial thinning, disruption of the myometrial wall, loss of the normal cleavage plane, and an inverted pear-shaped uterine configuration. Extrauterine involvement represents the most severe form of disease and is characterized by placental extension beyond the uterine serosa, abnormal placental tissue invading adjacent pelvic organs—most commonly the urinary bladder—irregularity or interruption of the bladder wall, nodular or exophytic placental masses, and prominent bridging vessels extending beyond the uterus. This compartment-based MRI assessment improves diagnostic accuracy, facilitates grading of placental invasion, and provides critical information for surgical planning in placenta accreta spectrum disorders. (Figure 12-18).

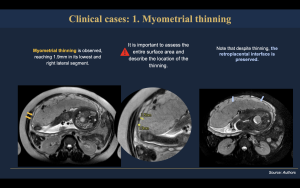

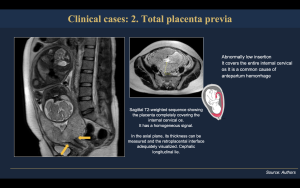

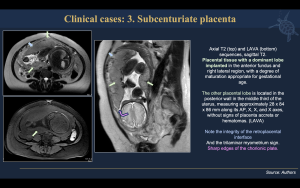

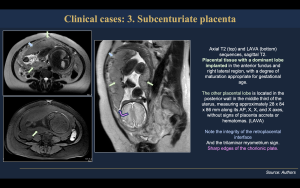

The following section presents representative clinical cases illustrating the spectrum of placental pathologies that may be encountered during magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. These cases highlight key imaging features across the placental compartments, emphasizing normal variants and pathologic findings that are essential to recognize in daily practice. A systematic MRI-based assessment allows accurate differentiation between physiologic changes and abnormal placental invasion, supporting correct diagnosis and optimal clinical management (Figure 19-25).