Introduction

The midgut plays a crucial role in the development of the digestive system, undergoing key embryological processes such as physiological herniation, rotation, and fixation within the abdominal cavity. Variations in these processes can lead to congenital anomalies with significant clinical implications, including malrotation, volvulus, omphalocele, gastroschisis, Meckel’s diverticulum, and intestinal duplications.

Diagnostic imaging is essential in the evaluation of the midgut, enabling early identification and characterization of these anomalies. Modalities such as plain radiography, contrast-enhanced studies, Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) serve as fundamental tools in clinical practice.

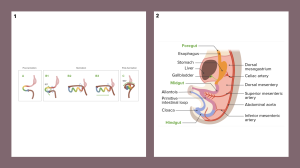

Embryology of the Midgut and Hindgut

Midgut

The midgut develops into the distal small intestine, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and right two-thirds of the transverse colon, supplied by the superior mesenteric artery (SMA).

By the sixth week, rapid intestinal growth causes physiological umbilical herniation. The midgut loop, with a proximal limb (small intestine) and a distal limb (cecum and ascending colon), undergoes a 90° counterclockwise rotation outside the abdomen, followed by an additional 180° rotation during retraction in the tenth week. The jejunum returns first, while the cecum and ascending colon settle in the lower right quadrant.

The duodenum and pancreas become retroperitoneal, while the ascending colon loses its mesentery. The cecum and appendix appear in the sixth week, with a retrocecal appendix in 64% of cases.

Hindgut

The hindgut forms the left third of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and upper anal canal, supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). The descending colon becomes retroperitoneal, while the sigmoid colon retains its mesentery.

Cloaca and Anal Canal

By the seventh week, the urorectal septum divides the cloaca into the rectum and anal canal dorsally and the urogenital sinus ventrally. The anal membrane ruptures in the eighth week.

The anal canal has a dual origin:

- The upper two-thirds (endoderm-derived) are supplied by the superior rectal artery and autonomically innervated.

- The lower third (ectoderm-derived) is supplied by the inferior rectal arteries with somatic innervation.

The pectinate line marks this transition (1).

Anatomy of the Jejunum, Ileum, and Large Intestine

The jejunum and ileum form the intraperitoneal portion of the small intestine, extending from the duodenojejunal flexure to the ileocecal junction. They measure approximately 6-7 meters, with the jejunum primarily in the upper left quadrant and the ileum in the lower right quadrant.

- Vascular supply: The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) provides jejunal and ileal branches, while venous drainage occurs via the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), contributing to the portal vein.

- Lymphatic drainage follows a sequential pathway from lacteals to superior mesenteric lymph nodes.

- Innervation: The superior mesenteric plexus, with sympathetic fibers from T8-T10 and parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve.

The large intestine extends from the ileocecal valve to the rectum, including the cecum, appendix, ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon, rectum, and anal canal. It is characterized by teniae coli, haustra, and omental appendices, with a primary function of water absorption and fecal formation.

- Vascular supply: the SMA and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Venous drainage occurs via the SMV and inferior mesenteric vein (IMV).

- Lymphatic drainage: Varies by region, reaching superior or inferior mesenteric lymph nodes.

- Innervation: The superior and inferior mesenteric plexuses, with sympathetic fibers reducing motility and parasympathetic fibers enhancing it (2).

Congenital Pathology of the Midgut

Congenital anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract encompass a wide spectrum of malformations, some evident at birth and others diagnosed later in childhood or adulthood. Diagnostic imaging plays a key role in their evaluation, with plain radiography, contrast studies, ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) being essential tools.

Classification of Neonatal Anomalies

Structural:

- Embryologic maldevelopment: midgut malrotation, duplication cysts, anorectal atresia.

- Intrauterine vascular complications: jejunoileal atresia, colonic atresia/stenosis.

Functional:

- Meconium ileus.

Mixed (structural-functional):

- Midgut volvulus (secondary to malrotation), colonic aganglionosis (3).

Duodenal Atresia

A congenital anomaly (1:6,000–1:10,000 live births) caused by failed duodenal recanalization (weeks 5–6 gestation). It is 10 times more common than pyloric atresia and frequently associated with trisomy 21 (≈33%) and other congenital anomalies (>50%). A genetic component is suspected but not confirmed. Morphological types include web, fibrous cord, or complete gap.

Jejunal Atresia

Results from fetal intestinal ischemia, leading to vomiting and abdominal distension. The “apple-peel” variant involves severe intestinal shortening and poor prognosis.

Ileal Atresia

Causes distal obstruction with absent meconium passage. Classified as:

- Type 1: Obstructing membrane.

- Type 2: Fibrous cord between segments.

- Type 3: Complete atresia with mesenteric defect.

- Type 4: Multiple atresias.

Meconium Ileus

A common manifestation of cystic fibrosis, caused by thick meconium impaction in the distal ileum, leading to abdominal distension and bilious vomiting. Complications include volvulus, perforation, and meconium peritonitis.

Meconium Peritonitis

A chemical peritoneal inflammation due to intrauterine bowel perforation, often from ileal atresia or meconium ileus. Imaging may show fibrosis and calcifications. In some cases, a meconium cyst forms, encapsulating inflammatory fluid.

Malrotation

Failure of normal midgut rotation during embryonic development results in:

- Non-rotation: small bowel on the right, colon on the left.

- Incomplete rotation: Failure of final duodenojejunal loop rotation.

- Reverse rotation: transverse colon posterior and duodenum anterior to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA).

Volvulus

A twisting of the intestine around its mesenteric axis, compromising vascular supply. Presents as acute abdominal pain and bilious vomiting, especially in neonates. It may be associated with Ladd’s bands, peritoneal structures that can cause obstruction even without volvulus.

Enteric Duplication Cysts

Most commonly found in the distal ileum, they may contain ectopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa, increasing the risk of bleeding, ulceration, or perforation. They can also act as a lead point for intussusception.

Abdominal Wall Defects

- Gastroschisis: right-sided abdominal wall defect with extruded bowel loops lacking a protective sac. Associated with short bowel, malrotation, atresia, and dysmotility.

- Omphalocele: Herniation through the umbilicus, covered by peritoneum and amnion. Frequently linked to cardiac defects, chromosomal anomalies, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, with higher mortality than gastroschisis.

Omphalomesenteric Duct Remnants

The omphalomesenteric duct connects the yolk sac to the fetal midgut and should close before birth. Its persistence leads to anomalies such as:

Meckel’s Diverticulum: The most common small bowel anomaly, arising from the antimesenteric border of the distal ileum. It may contain ectopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa, increasing the risk of ulceration, bleeding, and obstruction.

Described by the Rule of 2s:

- Present in 2% of the population.

- Located <2 feet from the ileocecal valve.

- Measures ~2 inches in length.

- May contain 2 types of mucosa.

- Becomes symptomatic in the first 2 years of life.

Other anomalies: umbilical fistula, omphalomesenteric sinus, and duct remnants may also occur.

Hirschsprung Disease

- 15-20% of congenital obstructions.

- Lack of ganglia → Aperistalsis, obstruction, proximal dilation.

- 1 in 5,000 births, more common in males.

- Rectosigmoid (75-80%), Total colon (8%).

- Barium enema: inverted cone transition (50% cases).

- Cross-section: dilated proximal (normal), narrow distal (aganglionic).

Anorectal Anomalies

Clinical Presentation:

- Manifest as signs of low colonic obstruction in the neonatal period.

- Congenital Associations (up to 40%):

- Renal, vertebral, esophageal, and tracheal anomalies.

Related Syndromes:

- VACTERL association: vertebral, anorectal, cardiac, tracheal, esophageal, renal, and limb anomalies.

- Currarino triad: combination of anorectal malformation, sacral anomaly, and presacral mass.

Imaging Studies:

- Males: Voiding cystourethrogram to assess genitourinary involvement.

- Females: vaginogram or fistulogram to evaluate potential fistulous connections with the colon (4).