Findings and procedure details

Omental biopsy in patients with suspected peritoneal carcinomatosis on CT and involvement of the greater omentum is a quick and safe method for achieving a definitive histological diagnosis, with reported diagnostic rates of around 95%.

Ultrasound (US) is the technique of choice for guidance, as it offers several advantages over CT, such as real-time visualisation, real-time compression, lower cost and no radiation exposure.

Procedure: Fig 2: Material required to perform the procedure.

Fig 3: Summary of the procedure.

1. Prior to the procedure, a thorough review and correlation between abdominal US and CT images is recommended to identify anatomical landmarks that will help us choose the best percutaneous approach. In this regard, mass-forming sites with larger nodules or greater thickness and density of the “omental cake” on CT are preferable, as they provide a better sample than regions with ill-defined reticular infiltration of the omental fat.

2. After identifying the optimal site for sampling, we place a marker on patient´s skin and administer subcutaneous anaesthesia up to the peritoneal fascia.

3. Next, we insert the biopsy needle and advance through the peritoneal fascia in an oblique direction, parallel to the probe and following the long axis of the greater omentum, until the tip of the needle reaches the anterior margin of the omental target. Once there, we take the sample while the patient holds their breath.

4. After the procedure, an US scan is performed at the biopsy site to rule out immediate complications, such as haematomas related to the needle trajectory. At our centre, we also keep the patients monitored for two hours to exclude delayed complications before discharging them.

Indications:

In the evaluation of peritoneal carcinomatosis, we can distinguish three patterns of omental involvement suitable for biopsy, which may coexist in the same patient:

a) Reticular or infiltrative pattern. Characterised by a poorly defined reticulation and stranding of the omental fat. Although often perceived as a pattern with low diagnostic yield, several studies have demonstrated that a core needle biopsy in this context may have a diagnostic performance comparable to that of mass-forming sites.

Fig 4: Peritoneal carcinomatosis with an ill-defined reticular or infiltrative pattern in a 56-year-old man with abdominal pain, distension and nausea.

(a) CT scan shows a reticulated and poorly defined omental involvement with interspersed fat (red arrows) and ascites (yellow asterisk).

(b) US scan shows hypoechoic infiltration of the omentum (red asterisk) mixed with hyperechoic areas of relatively preserved omental fat (green arrows).

(c) US-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy of the omental infiltration with a 14G needle was performed (white arrows), with a final pathological diagnosis of high-grade appendicular mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Fig 5: Reticular or infiltrative involvement of the greater omentum in an 71-year-old man with weight loss.

(a,b,c) CT scan in the portal phase shows ill-defined reticulation, stranding and subtle nodularity of the omental fat (red arrows), associated with moderate ascites (yellow asterisk), retroperitoneal lymphadenopathies (blue arrows), mesenteric homogeneous bulky mass with encasement of mesenteric vessels (yellow arrows) and left supraclavicular lymphadenopathies (green arrow). In this case, a greater omentum biopsy was ruled out, as it was considered to have limited diagnostic value given the characteristics of the omental involvement and the suspicion of a lymphoproliferative process (which requires significant material for adequate typification).

(d) US-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy of a left supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (green arrow) was performed instead using a 16G needle (white arrows), with a final pathological diagnosis of follicular lymphoma.

b) Nodular pattern. Presence of single or multiple nodules in the omental fat.

Fig 6: Peritoneal carcinomatosis with “nodular” pattern in an 73-year-old woman with abdominal distension.

(a) CT scan in the portal phase shows multiple nodules in the greater omentum (red arrows) of unknown origin, associated with ascites (yellow asterisk) and thickening of peritoneal sheets.

(b) US scan shows solid hypoechoic nodules in the omentum with well-defined margins.

(c) US-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy of an omental nodule using a 18G needle was performed (white arrows), with an initial suspicion of high-grade serous carcinoma of gynaecological origin. However, following immunohistochemical techniques, the definitive pathological diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL).

c) "Omental cake" pattern. Thick omental disease due to the confluence of nodules and masses.

Fig 7: Peritoneal carcinomatosis with “omental cake” pattern in a postmenopausal woman with abdominal distension and discomfort.

(a) CT scan in the portal phase shows dense and thick confluent disease in the greater omentum (red arrows) of unknown origin associated to ascites (yellow asterisk).

(b) US scan shows solid “omental cake” with moderate ascites, adjacent to the abdominal wall.

(c) US-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy of the “omental cake” using a 18G needle was performed (white arrows), with a final pathological diagnosis of primary peritoneal high-grade serous papillary carcinoma.

Fig 8: Incidental finding of peritoneal carcinomatosis with “omental cake” pattern in an 82-year-old woman with gastritis.

(a,b,c) CT scan in the portal phase shows dense and thick confluent disease in the greater omentum (red arrows) of unknown origin.

(d,e) US shows solid vascularised areas of “omental cake” on colour Doppler, adjacent to the abdominal wall.

(f,g) US-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy of the “omental cake” was performed using a 18G needle, with a final pathological diagnosis of primary peritoneal high-grade serous papillary carcinoma. Note how the needle tip was carefully placed at the anterior margin of the “omental cake” (green arrow) before taking the sample (white arrows).

In cases with mass-forming patterns (nodular, omental cake), a core needle biopsy with a caliber of at least 18 Gauge and two passes is recommended to ensure the sample is appropriate.

In cases with a poorly defined reticular infiltration of the omental fat or suspected peritoneal lymphomatosis, we suggest using a 16 or 14 Gauge needle for adequate pathological typification.

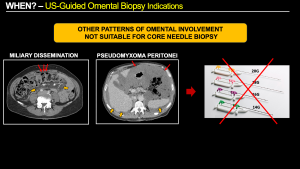

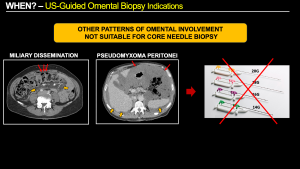

Other specific types of omental involvement include miliary dissemination (common in gastric cancer and unsuitable for core needle biopsy due to the tiny size of the implants) and pseudomyxoma peritonei (in which core needle biopsy is not recommended due to its low cellularity, abundant mucinous content that can dilute the sample, and the risk of needle tract seeding to the abdominal wall).

Fig 9: Other patterns of omental involvement on CT scan not suitable for core needle biopsy:

(a) Miliary dissemination. Example of gastric cancer with punctate nodules in the greater omentum representing tiny miliary implants (red arrows), and a slight increase in mesenteric fat density or “misty mesentery” (orange arrows) secondary to miliary and plaque-like disease. This type of omental involvement is not suitable for core needle biopsy due to the small size of the implants.

(b) Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. Example of high-volume pseudomyxoma with abundant mucin occupying the greater omentum (red arrows) and the rest of the abdominal cavity, causing a characteristic “scalloping” of solid abdominal viscera such as the liver and spleen (orange arrows). This type of omental involvement is not suitable for percutaneous core needle biopsy due to its low cellularity and the predominance of mucinous content, which can dilute the sample. There is also a risk of needle tract seeding to the abdominal wall.

Recommendations and potential complications:

Longitudinal alignment (in-plane) between the US probe and the needle is recommended for real-time guidance rather than a transverse view (out-of-plane), in order to allow adequate tracking of the needle path. We recommend an oblique trajectory that follows the long axis of the greater omentum, thus minimising potential damage to the mesenteric vessels and adjacent intestinal loops. The epigastric vessels, which can be easily identified with Doppler ultrasound, should also be taken into account.

Real-time compression is useful for reducing the distance to the omental target, stabilising the omental disease and displacing vulnerable structures such as bowel loops.

Ascites is not a major contraindication, but when it is abundant, drainage paracentesis is recommended prior to biopsy to reduce the distance to the omental disease and facilitate compression in case of post-biopsy bleeding.Fig 10: Peritoneal carcinomatosis with “omental cake” pattern in an 80-year-old woman with abdominal distension.

(a) Non-contrast CT scan due to renal failure, (b) T2-weighted MR image and (c) Diffusion-weighted MR image (b=800) show thick and solid omental disease at the level of the transverse mesocolon (red arrows) with abundant ascites (yellow asterisk).

(d) US scan shows the “omental cake” displaced posteriorly by the abundant ascites (red arrows), so paracentesis was performed prior to omental biopsy to facilitate the procedure and avoid complications. (e) US image after evacuation of the ascitic fluid shows anterior displacement of the “omental cake” (red arrows), which is now adjacent to the anterior peritoneal fascia.

(f) US-guided percutaneous core needle biopsy of the “omental cake” was performed (white arrows), with a final pathological diagnosis of primary peritoneal high-grade serous carcinoma.

Major complications, such as vascular injuries with active bleeding or intestinal perforation, are rare, and none have been reported at our centre after 15 years of experience with over 100 procedures performed. This absence of complications is consistent with the existing literature.

Limitations of the present study:

This educational poster is based on a single-centre experience, although a comprehensive review of the existing literature on omental biopsy has been carried out to support our recommendations and reduce bias.