Neurofibromas are characteristic of NF1. Cutaneous neurofibromas are present in 95% of patients, although they are not life-threatening. Deep neurofibromas are neoplasms of the peripheral nerve sheath and are divided into nodular neurofibromas (dependent on a single nerve fascicle) and PNF (dependent on several fascicles).

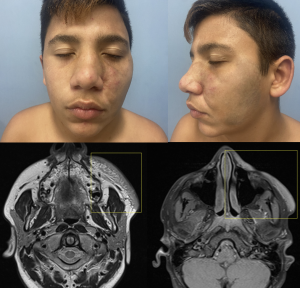

PNF are pathognomonic of NF1 and are present in 40–60% of patients. These tumours can affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue, causing aesthetic alterations, or they can involve deeper structures, leading to skeletal changes. On the other hand, they may degenerate into malignant transformation.

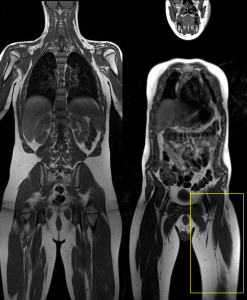

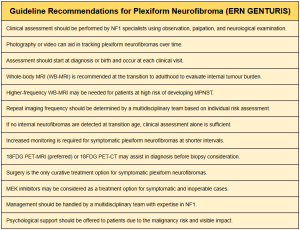

Regarding the early diagnosis of PNF, European guidelines such as ERN GENTURIS recommend performing whole-body MRI in asymptomatic adolescent patients with NF1, as this is the stage of life when PNF most commonly develops. This recommendation is based on the availability and speed of current imaging techniques, the rapid tumour growth and development of morbidity during childhood and adolescence, and the increasing number of therapeutic agents that may effectively halt neurofibroma growth. Additionally, the presence of the 17q11 microdeletion increases the risk of developing internal tumours.

For already diagnosed PNF, the guidelines recommend individualised monitoring led by multidisciplinary medical teams. Furthermore, symptomatic PNF requires more frequent monitoring and shorter intervals between imaging tests.

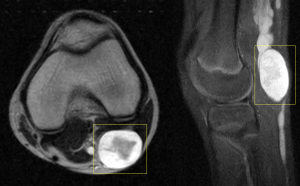

Differentiating nodular neurofibromas from PNF is crucial in imaging studies. Nodular neurofibromas are better defined and usually more superficial, making them suitable for ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and MRI. They typically appear as well-defined, oval lesions adjacent to the peripheral nerve, displaying the "target sign," with a hyperintense margin on T2-weighted sequences and a hypointense centre. After gadolinium administration, they show homogeneous enhancement of the central component.

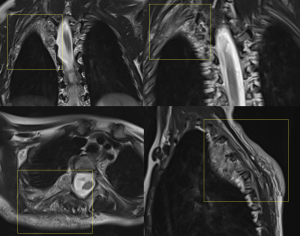

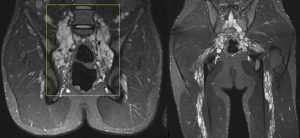

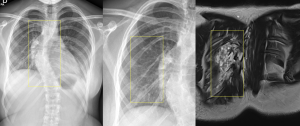

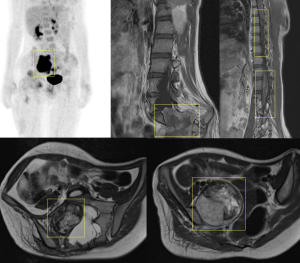

On the other hand, PNFs present as confluent, infiltrative, multinodular masses with a mass effect on adjacent structures, making MRI the imaging modality of choice. They may display multiple target signs and show heterogeneous enhancement after gadolinium administration. A structured report can categorise them based on their morphology and signal intensity (homogeneous, heterogeneous, or mixed patterns), depth (superficial, deep, or mixed), and relationship with adjacent structures (diffuse or well-defined).

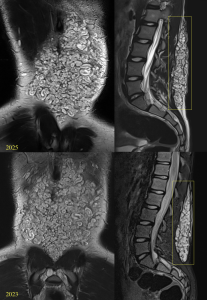

Regarding complications, various bone abnormalities are associated with mesodermal dysplasia and extrinsic pressure from neurofibromas.

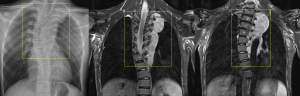

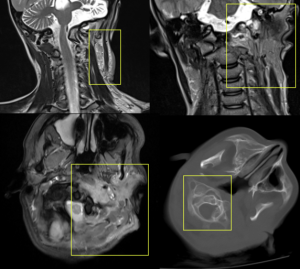

Among these, scoliosis is the most common, present in 21% of patients. Scoliosis can be non-dystrophic, following a course similar to that of the general population, or dystrophic, which occurs earlier, progresses rapidly, and has a worse prognosis. Dystrophic scoliosis involves four to six vertebral bodies and is associated with vertebral scalloping, neuroforaminal widening, transverse process spindling, and rib pencilling.

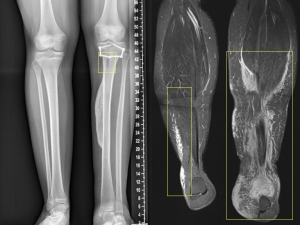

Other bone alterations associated with PNF include posterior vertebral fusions, thinning of vertebral components, widening of the neural foramina, rib deformities, and anterolateral deformities of the tibia and fibula.

PNF can degenerate into malignant neoplasms in 2% of cases, transforming into high-grade sarcomas (MPNSTs).

MPNSTs can present asymptomatically but are typically associated with symptoms such as persistent pain, rapid growth, hardening, or new-onset neurological deficits. Despite their low incidence, they are the leading cause of death in NF1 patients.

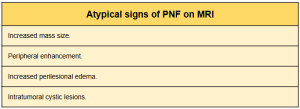

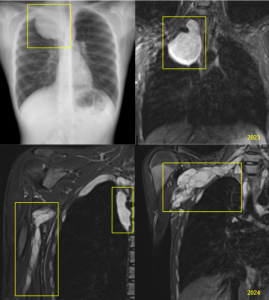

If MPNST is suspected, regional MRI should be performed. MPNSTs show atypical signs on MRI, such as increased mass size, peripheral enhancement, increased perilesional edema, and intratumoral cystic lesions. If two or more atypical signs are present, the suspicion of malignant transformation is high.

However, PET-CT or biopsy is often required for a definitive diagnosis. PET-CT is the most accurate imaging test, with MPNSTs appearing as hypermetabolic lesions with an SUVmax greater than 3.5.

Historically, the treatment for PNF has been surgical.

Indications for surgical treatment include the potential for malignant transformation, neurological deficits, aesthetic alterations, and respiratory difficulties (especially in PNF of the neck and mediastinum).

Studies have shown that the highest rate of benefits is achieved when treating PNF that causes respiratory alterations due to extrinsic compression and aesthetic changes.

However, a high recurrence rate of PNF after surgery, along with multiple functional and neurological sequelae, has also been demonstrated.

Therefore, it has been concluded that new, effective medical therapies are necessary for the treatment of PNF.

Currently, Selumetinib, a MEK inhibitor, has been approved for treating inoperable and symptomatic PNF. Selumetinib has demonstrated tumour reduction with a partial response in 70% of patients, with 59% of those showing durability after one year, and symptom relief lasting up to four years.

This drug is not absent of adverse effects, though most are mild (e.g., gastrointestinal symptoms, asymptomatic increase in CPK, paronychia, acneiform eruptions). To date, the drug dose has only been reduced in 39% of patients due to an asymptomatic reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).