This presentation examines the lymphatic dissemination patterns of various neoplasms, including hepatobiliary, gastrointestinal, urological, gynecological, neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma, melanoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), and sarcomas, utilizing PET/CT, CT, and MRI imaging techniques.

Classification of Lymph Node Metastases:

- Locoregional Metastases (N): Nodes near the primary tumor within direct lymphatic drainage, considered a local tumor extension. Specific nodal chains depend on tumor location. These nodes are seen as an extension of the tumor and typically involve specific nodal chains, depending on the tumor's location. For example, celiac nodes are associated with gastric cancer, while iliac nodes are connected to gynecological tumors [1,2].

- Distant Metastases (M): This refers to the involvement of lymph nodes outside the established regional territory, indicating that cancer has spread beyond the initial nodal chains. For instance, in the case of testicular cancer, the spread to lumboaortic nodes is classified as locoregional. However, when the supraclavicular Virchow node is involved, it is considered metastatic, a situation that rarely occurs without previous involvement of the lumboaortic nodes. [3,4].

Typical and Unusual Patterns:

Lymphatic spread differs by tumor type and location, exhibiting clear patterns and some notable exceptions.

- Typical Patterns: Spread occurs sequentially within the tumor's lymphatic territory, following a sequential order that adheres to the afferent and efferent vessels within the tumoral territory.

- Unusual Patterns: Lymph nodes may be found in unusual locations due to lymphatic spread from the metastases of a primary tumor or its extension to nearby tissues, ultimately affecting non-regional nodes. For example, an abdominal tumor can cause hilar pulmonary adenopathy if there are lung hematogenous metastases, or prostate cancer invading the rectum can exhibit lymphatic spread similar to rectal cancer.

Patterns of Neoplastic Dissemination

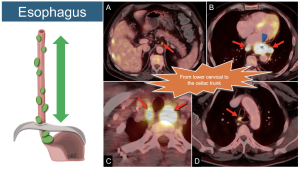

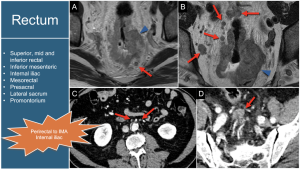

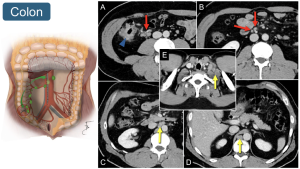

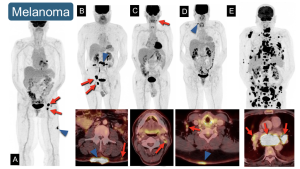

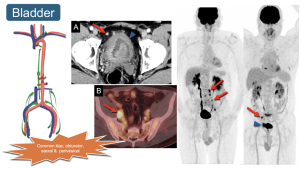

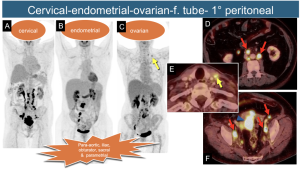

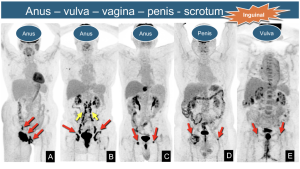

The primary neoplasm will be represented by a blue arrowhead, locoregional metastases by red arrows, and distant metastases by yellow arrows to clarify lymphatic pathways.

1. Esophagus: Regional nodes extend from the lower cervical region to the celiac trunk. All of these nodes are considered regional, regardless of the location of the primary tumor.

2. Stomach: Regional lymph nodes include perigastric nodes (12 stations) across the ligaments and adjacent to the vessels [1,2].

3. Rectum: Lymphatic regional drainage involves the mesorectum's superior, middle, and inferior rectal nodes. The inferior mesenteric axis is considered a regional area, which can appear relatively high on images and should not be mistaken for lumboaortic nodes, as those are metastatic [2,3]. Internal iliac nodes also indicate regional involvement.

4. Colon: Lymphatic involvement aligns with the tumor's location. For example, ileocolic and middle colic lymph nodes are regional to a right colonic tumor, whereas left colic and inferior mesenteric nodes are regional to a descending colon tumor. Retroperitoneal, retrocrural, and lower cervical nodes are distant metastases.

5. Melanoma: Since melanoma can develop in any location, it is essential to identify the specific regional drainage [3,5].

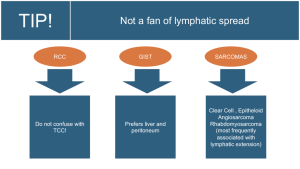

6. Renal: Renal cell carcinomas do not show a tendency to spread through the lymphatic system; their preferred route of dissemination is hematogenous, particularly to the lungs and bones, but they can also spread regionally through the renal hilum and lumboaortic nodes, other sites are considered metastatic.

7. Prostate:Regional lymphatic involvement progresses systematically, starting from the iliac vessels and their branches upward (external iliac, internal iliac, obturator, and sacral chains[4].

8. Bladder: Dissemination mirrors that of the prostate, involving the perivesical space and common iliac nodes as regional drainage.

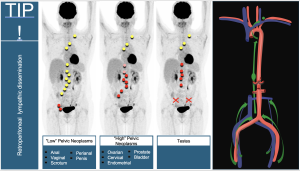

9. “High” Pelvic Neoplasms: Cancers of the cervix, endometrium, ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum share regional spread patterns involving para-aortic, iliac, obturator, sacral, and parametrial nodes. Involvement of left lower cervical (IV group) nodes renders them unresectable. Para-aortic nodes above the renal veins (suprarenal) are considered distant metastases in some studies [5,6].

10. “Low” Pelvic Neoplasms: Anal, vulvar, vaginal, penile, and scrotal cancers drain to inguinal nodes as regional sites. As midline neoplasms, they may show unilateral or bilateral lymph node involvement.

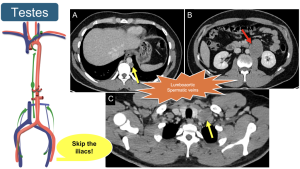

11. Testicular Cancer: Understanding lymphatic drainage via gonadal veins is essential, as it bypasses the iliac and inguinal nodes, directly affecting the retroperitoneum.

12. Summary of retroperitoneal lymphatic dissemination. The retroperitoneal lymphatic dissemination pathways vary depending on the origin of the neoplasm.

13. Pancreas: Their primary location influences the local dissemination of tumors. Tumors in the head and neck show patterns similar to those in distal biliary structures, often involving the superior mesenteric vessels, portal vein, and bile duct. In contrast, tumors located in the body and tail of the pancreas are more likely to affect the perisplenic lymph nodes and surrounding blood vessels. Any node located retroperitoneally below the level of the superior mesenteric artery is classified as metastatic.

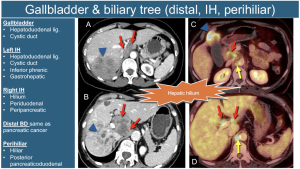

14. Gallbladder and Biliary Tract (Perihilar): Regional involvement varies by location, with the hepatic hilum nodes (including the hepatoduodenal and cystic duct nodes) being the most frequently affected.

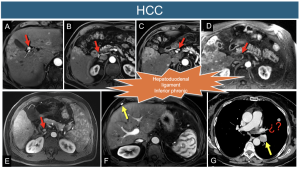

15. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): The lymphatic spread of this cancer usually follows the hepatoduodenal ligament and can involve the inferior phrenic nodes located between the right diaphragmatic crura and the adrenal gland. In cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), regional lymphadenopathy can often be observed in the hepatic hilum.

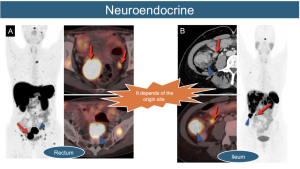

16. Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors: The lymphatic dissemination of these tumors is influenced by their origin, typically following a classic and orderly pattern. A key characteristic is the presence of classic mesenteric desmoplastic lymphatic involvement.

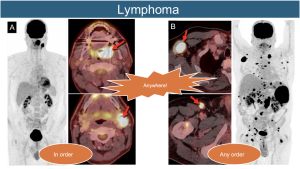

17. Lymphoma: Dissemination can occur anywhere in the body, following two patterns.

18. Tumors Without Lymphatic Predilection: