DEFINITIONS

Mesenteric ischemia, characterized by insufficient blood flow to the intestines, can present in acute or chronic forms, with acute mesenteric ischemia often representing a life-threatening emergency.

The spectrum includes:

- Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI): Thrombotic AMI, Embolic AMI, Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI), Venous AMI.

- Chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI).

ANATOMY

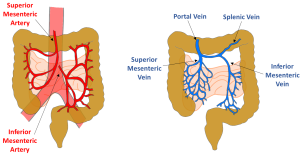

The small and large bowel receive blood supply from three primary arteries: the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) (Fig. 1). The celiac trunk supplies blood from the distal esophagus to the second part of the duodenum. The SMA covers the third and fourth parts of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and the colon up to the splenic flexure. The IMA supplies from the distal transverse colon to the upper rectum. The distal rectum is further supplied by the middle and inferior rectal arteries, which are branches of the internal iliac arteries.

There are mesenteric collateral pathways, including the gastroduodenal artery (connecting the celiac trunk and SMA), the marginal artery of Drummond, and the arcade of Riolan (both connecting the SMA and IMA).

Venous drainage mirrors the arterial system. The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) joins the splenic vein, which joins the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) to form the portal vein. Collateral venous pathways can also develop.

EMBOLIC ACUTE MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA

Arterial embolism is the most frequent cause of mesenteric ischemia (40%–50%). Cardiac origin is most frequent. Common sources include atrial thrombi from atrial fibrillation, mural thrombi post-myocardial infarction, and emboli from aortic plaques.

Clinical presentation: Sudden and severe abdominal pain. Symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, and initial diarrhea. As ischemia progresses to transmural infarction, the pain becomes diffuse. Emboli may also affect other organs, including the brain, kidneys, spleen, and extremities.

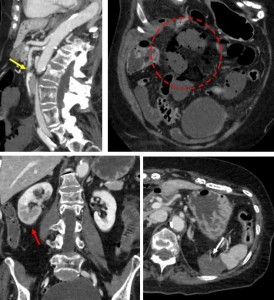

Imaging findings (Fig. 2): Non-enhanced CT may reveal hyperattenuating superior mesenteric artery emboli, while contrast-enhanced CT shows filling defects and superior mesenteric artery enlargement.

Reduced or absent bowel wall enhancement indicates impaired arterial supply, with ischemia progression leading to paralytic ileus, bowel wall thinning, intramural gas, and gas in mesenteric or portal veins. Advanced cases may exhibit extraluminal gas from bowel perforation.

THROMBOTIC ACUTE MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA

Arterial thrombosis is responsible for about 25% of acute mesenteric ischemia cases and is more common in patients over 70. It usually results from atherosclerotic disease in the visceral arteries. Bowel ischemia occurs when these arteries are severely stenosed or occluded, often exacerbated by hypotension or low cardiac output. Thrombotic AMI has a relatively slow progression compared to embolic AMI, as it is associated with the gradual development of collateral circulation.

Clinical presentation: The clinical symptoms of thrombotic AMI progress more slowly, with many patients reporting symptoms of mesenteric angina, nausea, early satiety, and weight loss. This results in “food fear,” where patients avoid eating due to the anticipated pain. In the acute phase, however, the clinical symptoms are similar to those found in patients with embolic AMI, including severe abdominal pain and signs of peritoneal irritation.

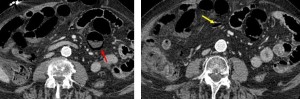

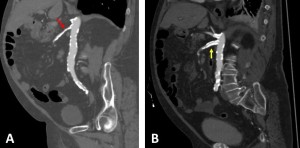

Imaging findings (Fig. 3): On imaging, thrombotic AMI typically presents with atherosclerotic calcifications at the SMA, celiac artery, and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Contrast-enhanced CT can demonstrate stenosis or occlusion at these sites, and collateral circulation pathways may be visible. Severe cases may show a "paper-thin" bowel wall, absence of bowel wall enhancement, mesenteric fat stranding, gas in the bowel wall and in the mesenteric and portal veins, and extrabowel gas.

NON-OCCLUSIVE MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA (NOMI)

Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) is a condition in which the intestines develop ischemia due to mesenteric vasoconstriction and reduced blood flow, typically seen in critically ill patients. Unlike other forms of mesenteric ischemia, such as arterial or venous occlusion, NOMI does not involve gross arterial or venous blockages but instead results from systemic factors like shock or vasopressor use. It is responsible for approximately 20% of mesenteric ischemia cases and is more common in older patients, often developing in the setting of circulatory shock, including septic, hemorrhagic, or cardiogenic shock.

Clinical presentation: NOMI often presents with acute or insidious abdominal pain, bloating, and abdominal distension, typically without defecation. In critically ill patients, these symptoms are often masked by sedation, ventilation, and other supportive measures. Additionally, occult blood may be present in stools, and signs of peritonitis or bowel perforation may develop in advanced cases.

Imaging findings (Fig. 4): The imaging diagnosis of NOMI is complex, as CT findings often overlap with other bowel diseases, such as infections or inflammatory conditions. Features suggestive of NOMI include narrowing of the origins of major mesenteric vessels, especially the SMA. Ischemic bowel segments on CT typically show lack of contrast enhancement, with areas of involvement being discontinuous and segmental. Advanced stages may show thinning of the bowel wall, fat stranding, ascites, the absence of bowel wall enhancement, gas in the bowel wall, mesenteric and portal veins, and extrabowel gas.

VENO-OCCLUSIVE MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA

Veno-occlusive mesenteric ischemia or venous acute mesenteric ischemia accounts for 5%–10% of all AMI cases and is more common in younger populations compared to other causes of AMI. It may be linked to various conditions such as hypercoagulability, cirrhosis, oral contraceptive use, deep venous thrombosis, or malignancy.

Clinical presentation: Veno-occlusive mesenteric ischemia presents with subacute abdominal pain that may persist over 2–4 weeks, along with symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal distension. Patients may experience fever and occult blood in stools.

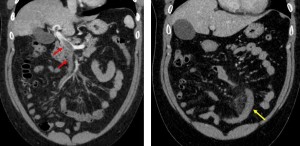

Imaging Findings (Fig. 5): Thrombi in the mesenteric and veins lead to venous obstruction, visible as luminal filling defects surrounded by rim-enhanced venous walls. Bowel wall thickening and mesenteric fat stranding are common, and the bowel wall may display a halo or target pattern of enhancement. In advanced cases, findings such as absent bowel wall enhancement, pneumatosis, portomesenteric venous gas, and extrabowel gas may be observed.

CHRONIC MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA

Chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) is a condition characterized by insufficient blood flow to the intestines, often caused by atherosclerosis in the mesenteric arteries. The condition can lead to AMI, which carries the risk of bowel infarction and death.

Clinical presentation: CMI often presents in patients older than 60. Symptoms develop gradually, with abdominal pain typically occurring 15–30 minutes after eating, lasting up to 30 minutes. The pain is often associated with weight loss, “food fear”, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Common risk factors include smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia.

Imaging findings: Diagnosis begins with clinical suspicion, supported by physical examination and laboratory tests. Imaging techniques play a critical role in confirming the diagnosis.

- Ultrasound: Duplex ultrasound is useful, though its accuracy can be limited by patient body habitus, bowel gas, and operator dependence. Fasting duplex criteria, such as a superior mesenteric artery peak systolic velocity above 275 cm/s, are indicative of significant stenosis.

- CT Angiography (Fig. 6A): This imaging method provides detailed assessment of stenosis or occlusion in the mesenteric arteries and can detect signs of ischemia like bowel wall thickening and pneumatosis. Multidetector CT offers fast scanning and 3D reconstruction, which helps evaluate collateral pathways.

- Magnetic Resonance Angiography: A non-invasive alternative to CT, useful for visualizing stenoses without radiation exposure, though it may not accurately assess the inferior mesenteric artery.

- Conventional Angiography: Direct visualization of vascular abnormalities and enabling pressure measurement to assess the hemodynamic significance of stenoses.

Treatment:

- Medical Treatment: Reserved for patients who are not candidates for surgery or endovascular intervention. It typically includes long-term anticoagulation therapy and occasionally nitrate therapy for symptom relief.

- Surgical Repair: Open surgical options, such as bypass grafting or endarterectomy, are associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates compared to endovascular approaches.

- Endovascular Repair (Fig. 6B): Angioplasty and stent placement offer a minimally invasive alternative to surgery, with high success rates (90–100%) and lower complication rates.