Preoperative Imaging

Key radiographic findings in GERD patients undergoing evaluation include:

- Esophageal Peristalsis: Up to 50% of GERD patients exhibit nonspecific motility disorders, which may improve postoperatively. Identifying achalasia or scleroderma preoperatively is crucial, as fundoplication in these patients often results in poor outcomes. [6]

- Hiatal Hernia: Accurate identification of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) and diaphragmatic hiatus is essential. Large hernias may indicate a shortened esophagus, necessitating esophageal lengthening via Collis gastroplasty. [7]

- Shortened Esophagus: Suggested by a hiatal hernia that does not reduce when the patient is upright. Failure to address this can lead to recurrent herniation and failed fundoplication. [7]

- Gastroesophageal Reflux: Although barium esophagography is not highly sensitive, it provides useful information on reflux severity, volume, and clearance time. [6,7]

- Complications of GERD: Including strictures and adenocarcinoma. [8]

Postoperative Imaging

An upper gastrointestinal series with water-soluble contrast should be performed immediately after surgery to rule out leakage, assess esophageal emptying, and confirm wrap placement.

Follow-up barium studies are crucial for evaluating fundoplication outcomes, particularly in patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms such as dysphagia or heartburn. [7,9,10]

Symptoms alone are unreliable for diagnosing recurrent reflux, as anatomical failures may occur even in asymptomatic patients. [8] When reflux symptoms persist postoperatively, fundoplication failure should be suspected. [7]

A minimum of 50 mL of contrast should be administered. Standard views include erect anteroposterior and oblique projections, with additional prone oblique and supine anteroposterior views for better visualization. [10] The radiology report should describe post-surgical anatomy, fundoplication integrity, esophageal motility, and the presence of reflux. [6,8]

A successful Nissen fundoplication should appear as follows on fluoroscopic imaging [3, 6-8]:

- A well-defined, symmetric, smooth fundic wrap, appearing as a pseudotumor at the medial aspect of the gastric fundus, less than 3 cm in length

- A narrowed but patent distal esophagus with a gentle curve through the wrap

- No distortion of the barium column

- The wrapped segment positioned below the diaphragmatic hiatus, with no hiatal hernia recurrence

- Absence of obstruction, reflux, or anatomical distortion

Postoperative Complications and Radiological Signs

Failed fundoplication can be categorized based on changes in wrap integrity, position, lumen patency, length, or recurrence of a hiatal hernia. [6]

Common complications include [6,7,11]:

- Tight Fundoplication: An excessively tight or long (≥2 cm) wrap causing dysphagia and bloating. Imaging shows smooth narrowing of the distal esophagus with delayed clearance.

Fig 2: Tight Fundoplication: Anteroposterior view from a barium study. The wrap extends more than 2 cm, resulting in functional obstruction, as evidenced by smooth narrowing of the distal esophagus and prolonged barium retention. This finding is consistent with an overly tight fundoplication. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa

Fig 2: Tight Fundoplication: Anteroposterior view from a barium study. The wrap extends more than 2 cm, resulting in functional obstruction, as evidenced by smooth narrowing of the distal esophagus and prolonged barium retention. This finding is consistent with an overly tight fundoplication. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa - Patulous or Incompetent Repair: The wrap is intact but too loose, failing to provide an effective barrier. Barium imaging reveals reflux without hiatal hernia recurrence.

- Disrupted Wrap (Hinder type I failure): Partial or complete breakdown of the fundoplication, often leading to recurrent hiatal hernia. Imaging shows a small or absent fundal defect.

Fig 3: Disrupted Wrap (Hinder Type I Failure): Anteroposterior view of an esophagram. Recurrent hiatal hernia is visible (yellow arrow), with the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (white arrowhead) and infradiaphragmatic stomach (yellow arrowhead) clearly identified. The absence of a fundal defect suggests a breakdown of the fundoplication. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa

Fig 3: Disrupted Wrap (Hinder Type I Failure): Anteroposterior view of an esophagram. Recurrent hiatal hernia is visible (yellow arrow), with the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (white arrowhead) and infradiaphragmatic stomach (yellow arrowhead) clearly identified. The absence of a fundal defect suggests a breakdown of the fundoplication. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa - Stomach Slippage above the Diaphragm (Hinder type II failure): The wrap remains intact and infradiaphragmatic, but the proximal stomach slips into the chest, usually due to suture breakdown. Imaging reveals a fundal defect below the diaphragm, with herniated stomach in the chest.

Fig 4: Stomach Slippage Above the Diaphragm (Hinder Type II Failure): Anteroposterior view of the distal esophagus and stomach. The stomach has slipped above the diaphragm due to probable disruption of esophageal sutures, while the wrap remains intra-abdominal. This configuration suggests a Type II failure. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa

Fig 4: Stomach Slippage Above the Diaphragm (Hinder Type II Failure): Anteroposterior view of the distal esophagus and stomach. The stomach has slipped above the diaphragm due to probable disruption of esophageal sutures, while the wrap remains intra-abdominal. This configuration suggests a Type II failure. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa - Slipped Wrap (Hinder type III failure): Slippage of the proximal stomach through the intact wrap creates a pouch below the diaphragm without hiatal hernia recurrence. Imaging shows an hourglass appearance, where the stomach is incorrectly encircled by the wrap.

Fig 5: Probable Slipped Wrap (Hinder Type III Failure): Anteroposterior view of a patient in the decubitus position. The stomach (white arrow) is encircled by the wrap, creating an hourglass configuration. This appearance suggests a slipped wrap, where the stomach, rather than the esophagus, is passing through the fundoplication. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa

Fig 5: Probable Slipped Wrap (Hinder Type III Failure): Anteroposterior view of a patient in the decubitus position. The stomach (white arrow) is encircled by the wrap, creating an hourglass configuration. This appearance suggests a slipped wrap, where the stomach, rather than the esophagus, is passing through the fundoplication. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa - Transdiaphragmatic Wrap Herniation (Hinder type IV failure): The entire intact wrap migrates into the chest through the diaphragmatic hiatus due to suture failure. Imaging shows the wrap and distal esophagus above the diaphragm.

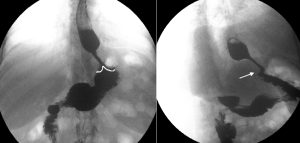

Fig 6: Transdiaphragmatic Wrap Herniation (Hinder Type IV Failure): Anteroposterior and lateral views of the same patient. The gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (white arrowhead) is located above the diaphragm, with the intact wrap (white arrows) filling with barium. The wrap has migrated into the thoracic cavity, leading to recurrent reflux and dysphagia. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa

Fig 6: Transdiaphragmatic Wrap Herniation (Hinder Type IV Failure): Anteroposterior and lateral views of the same patient. The gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) (white arrowhead) is located above the diaphragm, with the intact wrap (white arrows) filling with barium. The wrap has migrated into the thoracic cavity, leading to recurrent reflux and dysphagia. Reference: Department of Radiology, ULS São José, Lisboa

Reoperation After Failed Nissen Fundoplication

Reoperation is indicated for persistent or recurrent symptoms due to confirmed anatomical or functional defects, typically occurring within 15 months postoperatively. [4,5,11]

Most reoperations follow failed Nissen fundoplications, with wrap herniation being the most common issue, followed by tight, slipped, disrupted, or malpositioned wraps. [4,5] Laparoscopic redo fundoplication is effective, with symptom resolution in up to 89% of cases. [5]