CT Protocol

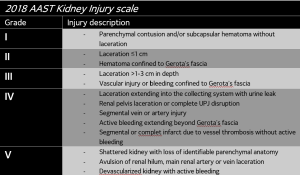

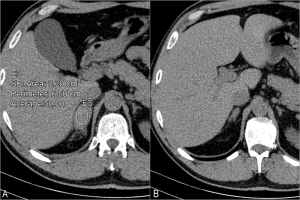

An appropriate CT protocol is essential to accurately depict organ injuries resulting from abdominal trauma. Historically, the standard trauma protocol has included a sing portal venous phase acquisition performed 65–80 seconds after intravenous injection of contrast, but the 2018 AAST Injury Scale advocates for the use of dual-phase CT (arterial and portal venous phases). Images should be reviewed by the radiologist to decide whether a delayed venous phase is needed (to exclude renal collecting system injury, for example). Delayed imaging is not included by default in the standard protocol in the attempt to limit radiation and increase time efficiency while studying critically ill patients.

Hypoperfusion complex

CT findings provide a general overview of the patient’s hemodynamic status. A list of findings has been associated with hypovolemia and imminent shock, including:

- collapsed IVC

- decreased caliber of the aorta

- thickening and hyperenhancement of the small bowel

- increased enhancement of the kidneys and adrenal glands

- decreased enhancement of the spleen

Bowel injury

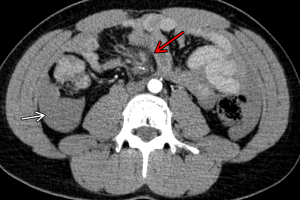

Damage to the mesentery or hollow viscera occurs in approximately 1–6% of patients with blunt abdominal trauma and CT signs of these injuries are often subtle and not specific. These include focal bowel wall thickening, stranding of the mesentery, free intraperitoneal fluid and extraluminal gas. Diffuse bowel-wall thickening, on the other hand, is more likely related to shock-bowel syndrome in the context of systemic hypoperfusion. Findings more specific of mesenteric injuries include extravasation of contrast-enhanced blood, abrupt termination of mesenteric vessels or hematomas, but these are usually absent.

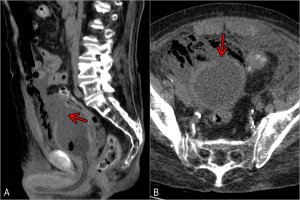

Half of the bowel injuries involve the small bowel, most frequently the proximal jejunum. Duodenal injuries (fig. 2) occur in the setting of a blow to the upper abdomen (for example, a steering wheel or bicycle handlebar) with patients presenting with epigastric pain and vomiting.

Solid Viscera Injury

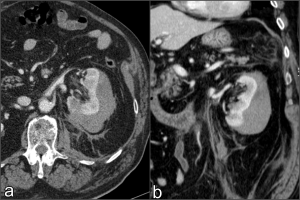

- Liver

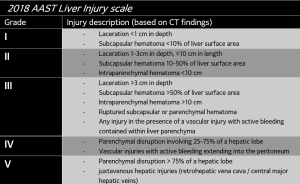

Traumatic damage to the liver is most often managed non-surgically and lacerations are the most common injury type. Higher grade injuries to the liver are the most common cause of death in severe abdominal trauma and the right lobe is more frequently involved due to its larger size and fixed position. As with the kidneys and spleen, the AAST injury scale is often applied to define the severity of injuries and guide management.

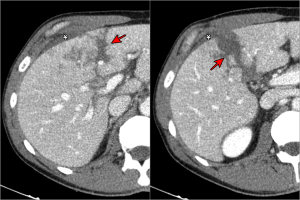

Lacerations appear as linear hypodensities often with a branching pattern. A deep laceration extending between two margins of the liver results in an hepatic fracture, which may cause lobar or segmental fragmentation with devascularization. Injuries affecting the bare area of the liver, not covered by peritoneum, in its posterior superomedial aspect, may result in large retro-peritoneal hematomas.

Vascular injury is defined as a pseudoaneurysm or arteriovenous fistula, which appear as a focal collection of vascular contrast that decreases in attenuation in the portal venous-phase. Active bleeding from a vascular injury, on the other hand, increases in size or attenuation in delayed phase.

A variety of liver masses can also present with hemorrhage in the setting of trauma (fig.6).

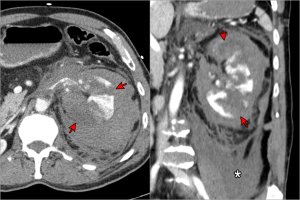

- Spleen

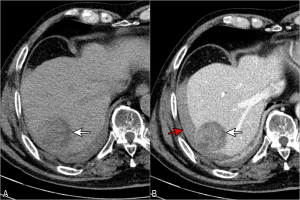

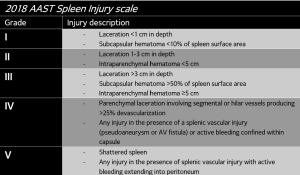

The spleen is the most frequently injured organ following abdominal trauma. Since the spleen plays a crucial role in immune function, 90% of the injuries are managed nonoperatively (mostly grade I-III) and active hemorrhage is the most important predictor for failure of conservative management.

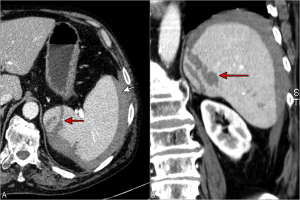

On CT, splenic lacerations and hematomas are readily identified as linear defects or relatively hypoattenuating areas in the parenchyma. The spleen often shows lobules and clefts which are normal anatomic variants and should not be misinterpreted as splenic laceration following trauma. Its heterogeneous parenchymal enhancement in the arterial phase must also not be mistaken for traumatic injuries.

- Kidney and bladder

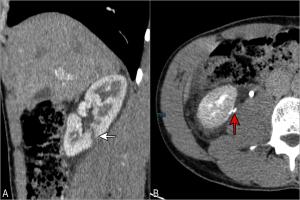

The kidneys are relatively well protected organs due to their retroperitoneal location, shielded by the abdominal viscera anteriorly, back muscles and spine posteriorly and the lower rib cage. Findings that should raise suspicion for renal trauma include hematuria, flank or upper abdomen pain or hematomas, abdominal tenderness or distention, palpable mass, ecchymosis or abrasions, rib fractures, hypotension and shock.

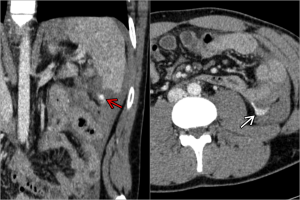

Renal contusions are defined as ill-defined areas of relatively poor contrast enhancement during the portal venous phase. The 2018 AAST update reflects that these injuries (previously diagnosed clinically by the presence of hematuria without evidence of injuries on other studies) can be visualized at multidetector CT.

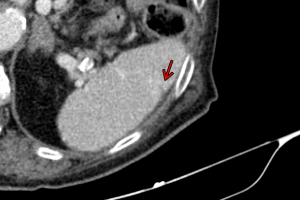

Subcapsular hematomas (fig.11) represent non-enhancing, superficial, crescentic or lentiform fluid collections contained within the renal capsule, while perinephric hematomas occur after laceration of the renal capsule, with blood accumulating between the renal parenchyma and Gerota and Zuckerkandl fascias.

Vascular injuries denote a grade III injury and vascular injuries with active bleeding from the main artery or vein result in a grade V injury).

In the presence of grade II or higher lacerations, low attenuation perirenal fluid or macroscopic hematuria, delayed CT images are useful to determine the integrity of the renal collecting system and exclude leakage of the opacified urine into the perinephric space (fig.12). AAST grade III, IV, and V injuries must be communicated to clinicians as they may require urgent urologic or endovascular management.

A kidney with preexisting abnormality, whether a renal mass, cyst or any anatomic abnormality, is at increased risk for injury. Renal cyst rupture (fig. 17) or intracystic hemorrhage (fig. 18) are unusual findings following traumatic injuries. Supportive treatment is most often indicated in these cases.

Bladder ruptures (fig. 19) usually occur in the context of a direct high-energy impact when the patient has a distended bladder. It can be intraperitoneal, extraperitoneal or a combination of both. Intraperitoneal rupture requires surgical treatment.

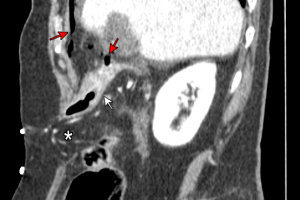

- Pancreas

Traumatic pancreatic injuries are uncommon, occurring in only about 2% of trauma patients, mainly due to its shielded location in the anterior pararenal space of the retroperitoneum. They are often overlooked due to low frequency of occurrence, subtle findings and associated multiorgan trauma.

These injuries are caused by deep anterior to posterior forces compressing the pancreas against the spine, hence the classic handlebar injury mechanism in the pediatric population.

Traumatic injuries to the pancreas are classified as contusion, laceration or transection and the neck and body are most frequently involved. Ductal involvement implies higher risk of complications and mortality, with lacerations involving >50% of the pancreas thickness usually resulting in ductal damaged.

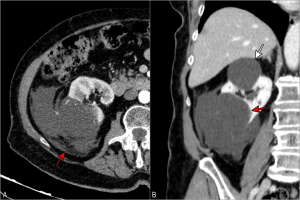

- Adrenal gland

Traumatic lesions of the adrenal gland are relatively common and usually associated with ipsilateral injury of other abdominal organs, occurring mainly due to lateral compression.

Adrenal injuries usually present as slightly hyperattenuating (mean attenuation of ~52HU) ovoid lesions. Since incidental adrenal findings are common, differentiating between an hematoma and a preexisting lesion may require follow-up imaging, usually showing resolution of the hematoma.

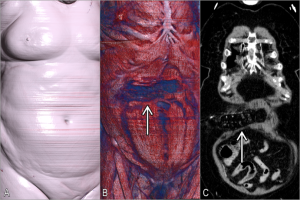

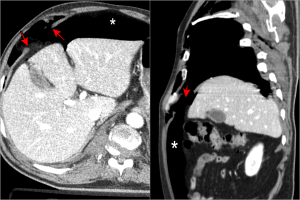

- Diaphragmatic rupture and abdominal wall injuries

Diaphragm tears result from discontinuity in the fibers of the membrane, commonly from a forceful lateral impact. It is more frequent on the left side and the rupture is usually >10cm. The “discontinuous diaphragm sign” is the most common and specific finding (fig.23).

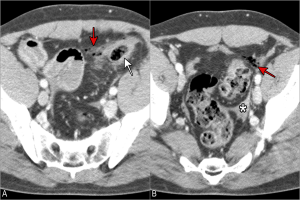

Abdominal wall injuries range from minor contusions to evisceration of abdominal contents due to wall rupture, but they are often overlooked due to the absence of signs at physical examination. Although its damage is uncommon, it has a strong association with other significant intraabdominal injuries.

They range from abdominal wall contusions (with a characteristic pattern of fat-stranding that mimics the contact of the seat-belt with the body), hematomas, muscle strains or tears, to abdominal wall hernias (fig. 24). The latter are the most severe traumatic injury and can happen anywhere along the abdominal wall, more commonly in the inferior lumbar triangle. These are associated with bowel injury in 50% of the cases.