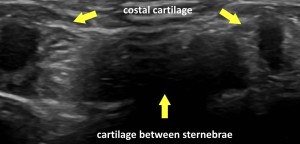

The sternum is located in the middle line of the anterior chest wall and it consists of the manubrium, the body or mesosternum and the xiphoid process. During its embryological development, the mesosternum originates from four segments (also called sternebrae), each consisting of one or two ossification centres. These ossification centres articulate with each other gradually, until puberty (up to 6-12 years of age) and some of them - especially the caudal ones - later in early adulthood [4]. Knowing the developmental stages of the sternum and its anatomical features across childhood, plays a central role in accurate diagnosis of anatomical variants versus sternal fractures, since both entities share common features.

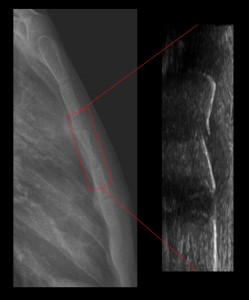

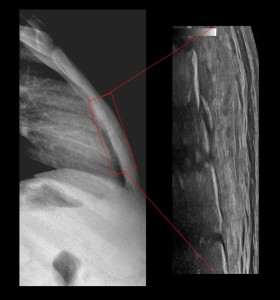

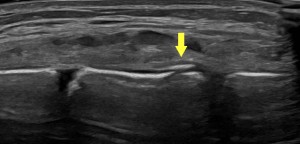

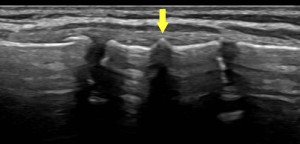

All images are sourced from our recent database and refer to six children (aged 4 - 12 years), who presented to the Emergency Department of our hospital with localized pain in the anterior chest wall, after direct injury. A lateral sternum x-ray was performed as an initial imaging examination, showing signs of a focal sternal fracture in the body of the sternum. The radiograph was accompanied by a complementary ultrasound examination, which confirmed the presence of a sternal fracture in all cases. During the sonographic examination, the patients were in supine position, a linear probe (2-9 MHz) was used and both transverse and longitudinal views of the sternal surface were obtained.

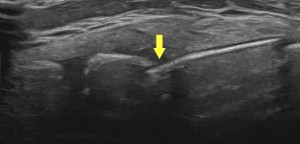

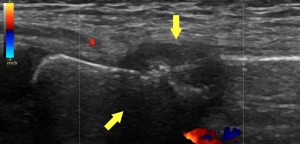

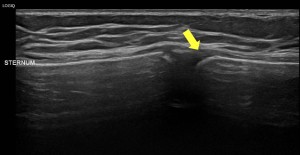

A comparison of the two modalities made it possible to identify the special sonographic features of sternal fractures, and the characteristics that differentiate them from the normal ossification centres of the sternum. In summary, the main sonographic features of sternal fractures, as they are shown in the figures, are the following:

- discontinuity of the cortical bone of the sternum

- angulation of the boundaries of the cortical bone

- sharp-edged projection of cortical bone

- accompanying hematoma or oedema in the region surrounding the fracture

All of the above features may not always be simultaneously identified in every sternal fracture and can appear in different combinations - a statement that is in agreement with our limited experience derived from our cases.

It is also important to keep in mind that any discontinuity of the cortical bone of the sternum is not suggestive of a fracture. For example, ossification centres of the sternum can be falsely interpreted as a discontinuity of the bone, but their edges are smooth and the “gap” between them is filled with connective tissue (cartilage). Moreover, there are also other fracture-mimicking anatomical variations of the sternum, such as the sternal foramen (which arises from the incomplete fusion of the cartilaginous neonatal sternum), suprasternal bone, sternoxiphoid pseudoforamen, sternal and manubrial cleft (in order of incidence) [5].

However, any lesion identified in an unexpected location, excluding the expected “gaps” of the connective cartilage, should be alarming - suggesting a possible sternal fracture - and should be assessed carefully and in correlation with the patient’s clinical characteristics.

The sonographic appearance of sternal fractures can provide plenty of information, mostly because of the superficial position of the sternum. Εspecially in cases of minimal displacement, sonography can be proven to be a more sensitive and specific diagnostic method compared to plain radiography [1]. Ultrasound is also an easily accessible and safe method, without ionizing radiation and can be applied bedside to multi-injured patients, with no need of mobilization [6]. Moreover it can unveil accompanying lesions or pathologies of the surrounding tissues, such as hematomas, pneumo- or hemothorax and pericardial effusion, allowing a better assessment of the injury. However, sonography is a provider-dependent method and may cause discomfort to the patient, because of the pressure applied upon the wounded surface. The sequential imaging during the sonographic examination can also be occasionally overwhelming, especially when conducted by an inexperienced radiologist, potentially leading to false-negative results. On the other hand, lateral sternum radiography still remains the diagnostic gold standard, due to its fast, painless and comprehensive depiction of the thorax and its bone structures.