Radiographic imaging remains an essential tool in the diagnosis and monitoring of AS, providing clear indications of early inflammatory changes and advanced bony fusion.

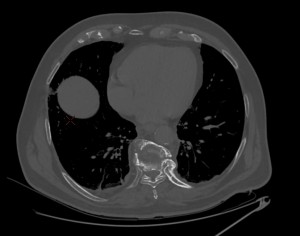

While radiography is crucial in detecting structural changes, CT imaging offers a more detailed and precise visualization of bony structures, allowing for better identification of subtle erosions and ossifications. It is especially useful in evaluating the progression of spinal ankylosis and sacroiliac joint involvement, helping clinicians monitor disease progression and treatment responses.

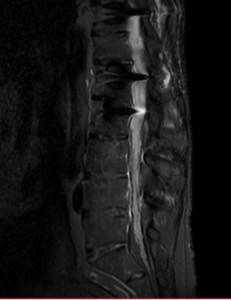

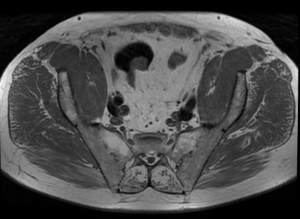

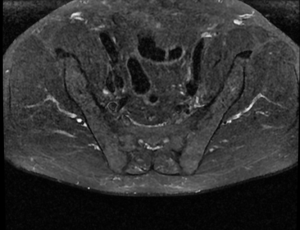

MRI is an invaluable tool for detecting early inflammatory changes in the disease process that may not yet be visible on plain radiographs. In particular, MRI provides superior sensitivity for identifying edema in the vertebral corners and sacroiliac joints and changes in soft tissues, such as ligamentous ossification and disc degeneration. Additionally, MRI is crucial for detecting associated complications, including spinal fractures, spondylodiscitis (Andersson lesions), and sacroiliitis, which can significantly impact treatment strategies. [2]

Both radiographically, as well as on CT and MRI, the primary key signs that we can identify in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) at the spinal level are inflammatory changes at the entheses, which progress with edema and erosions at the vertebral corners. In response, osteosclerosis develops at this level, which is radiologically represented as the "Shiny corner sign" or "Romanus lesion", which it is characterized radiographically or on CT by triangular areas at the vertebral corners with an osteosclerotic or osteocondensing appearance , and on MRI by hypointensity on T1 and hyperintensity on STIR (early edematous changes), which later evolve with lipid degeneration, showing hyperintensity on T1. [3][4]

As these changes progress, the concavity of the anterior edges of the vertebral bodies loses its concavity at multiple levels, which is radiologically identified as vertebral body squaring.

Another change that may occur in ankylosing spondylitis as a result of chronic inflammation is the calcification inside a spinal ligament or the annulus fibrosus, which manifests as marginal bony outgrowths with a vertical orientation, known as syndesmophytes.

Over time, these can fuse, forming bony blocks which, together with the other described changes, give a radiologic appearance of a "bamboo spine." This is one of the pathognomonic signs of ankylosing spondylitis.

As the disease progresses, a series of spinal ligaments, joints, and discs ossifications may occur. A notable imaging sign visible on radiography, CT, or MRI is the "Dagger sign," characterized by the ossification of the interspinous ligament in the frontal plane. A particular feature of MRI is that enhancement of the interspinous ligaments indicates enthesitis.

There are also specific imaging changes in AS related to sacroiliac involvement, which sacroiliitis changes can quantify according to the New York or ASAS criteria. This is an essential hallmark of SpA, initially characterized by edematous inflammatory changes that precede structural modifications, visible on MRI (T1 hypointensity, STIR hyperintensity), synovitis, and capsulitis (on gadolinium-enhanced T1). As sacroiliitis progresses, erosions develop, which may initially present as pseudo widening of the joint, detectable on radiographs, CT, and MRI, followed by subchondral osteosclerosis and proliferative changes, ultimately resulting in ankylosis.

To a lesser extent, AS also affects peripheral joints such as the hip (coxofemoral), knee, shoulder (scapulohumeral), and hand joints, as well as causing various erosions and fusions of the sternoclavicular, costochondral, and costovertebral joints. One of the specific radiological signs of AS affecting the shoulder is the "hatchet" deformity, defined by a well-circumscribed erosion on the lateral-dorsal aspect of the humeral head, resulting in a characteristic hatchet-like shape. [2] [3] [4]

From a complication standpoint, several specific radiological signs exist, such as Andersson lesions (called rheumatic spondylodiscitis), as a result of persistent inflammatory changes at the disc-vertebral level, which is characterized radiographically and on CT by irregularities and erosions of the vertebral endplates at the central level, and on MRI by disc-vertebral signal changes, with hyperintensity on STIR and hypointensity on T1 (often hemispherically shaped). [4] [5]

Due to chronic inflammatory status and extensive ossifications, patients with AS are significantly more prone to complications such as fractures, even in cases of minor trauma. One particularly specific type of fracture is the "chalk stick" or "carrot stick" fracture, which commonly occurs in the lower cervical or upper thoracic spine. [4] [5]