To evaluate acute dyspnea, we must follow an appropriate systematic approach. We propose this example:

1. Airways:

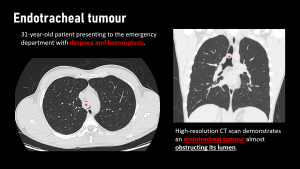

- Tumours

More than 90% of tracheal tumours are malignant, the most frequent being squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Metastatic involvement is less common and is usually due to local progression of nearby tumours. They present with non-specific symptoms such as dyspnoea and stridor. [1]

- Mucous impaction

Mucus plugs can be central or peripheral and are fluid dense with gas sometimes present. Some endobronchial tumours may simulate mucus plugs. [1]

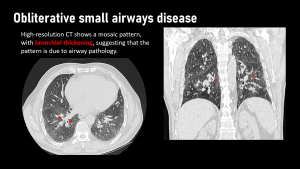

- Small airway disease

Small airway involvement is usually a component of other diseases such as bronchiolitis obliterans, emphysema, bronchiectasis and others. The most common form is smoker's bronchiolitis, although this is usually not clinically relevant. It may present with dyspnoea and cough, and imaging findings may include centrolobular nodules, mosaic attenuation pattern, with thickening of the bronchial walls, findings suggestive of airway pathology. [1,2]

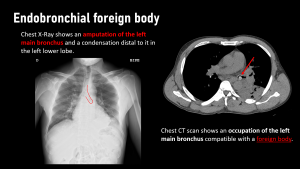

- Foreign bodies

It usually affects children under 4 years of age. Foreign bodies tend to settle in the right bronchial tree because it is larger and more vertical than the left.In the image we can see amputation of the bronchus and the absence of changes in the volume of the lung in expiration. [1]

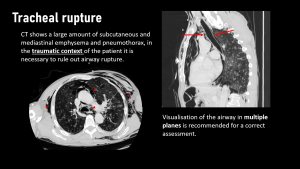

- Tracheal rupture

Tracheal involvement in trauma is rare and is associated with severe trauma with multiple findings. The location of the injury varies with the traumatic mechanism, being more cranial in penetrating trauma and more caudal in blunt trauma. [1,3]

2. Lung parenchyma:

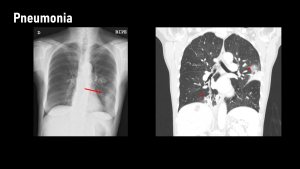

- Infectious

The manifestations can be very variable, from peribronchial nodules, ground glass, budding tree to alveolar condensation.The specific diagnosis of a pulmonary infection is not radiological, although there are radiological manifestations that in certain contexts allow us to orientate a specific aetiology. [1]

- Lung abscess

CT findings of a pulmonary abscess typically include a thick-walled cavity with a necrotic or fluid-filled centre, often containing an air-fluid level if it communicates with the airway. There is usually peripheral wall enhancement after contrast administration, and the surrounding lung may show consolidation or perilesional oedema. In more advanced cases, the infection can extend to the pleura, leading to pleural thickening, effusion, or even empyema. [1]

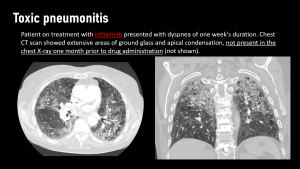

- Toxic pneumonitis

The lung is one of the organs that most frequently presents adverse reactions to the administration of any drug, and its frequency is increasing due to the greater use of new therapies such as monoclonal drugs.Its diagnosis can be difficult due to the low specificity of imaging, with the history of drug administration and comparative analysis with previous studies being useful for diagnosis. [4]

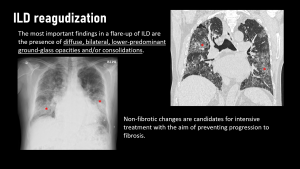

- Interstitial lung disease exacerbation

An exacerbation of interstitial lung disease is an acute worsening of respiratory function in patients with pre-existing fibrotic lung disease, often without an identifiable trigger. On CT, acute findings that may be amenable to treatment include new or worsening diffuse ground-glass opacities, often with superimposed reticulation or consolidation, predominantly in the lower lobes. Traction bronchiectasis and signs of fibrosis may also be present. The absence of infection, oedema or other alternative causes helps to confirm the diagnosis. In some cases, honeycombing and volume loss may also be seen, reflecting underlying chronic lung disease. [1]

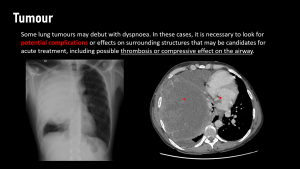

- Lung tumours

Lung tumours may sometimes debut as dyspnoea, with central position or obliteration of the bronchi being reasons for this, peripheral ones being less symptomatic. The most common central tumours are squamous cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma. [1]

3. Pleural cavity

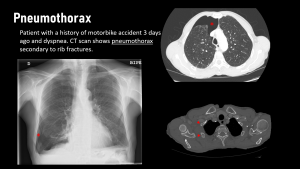

- Pneumothorax

Pneumothorax appears on CT as air in the pleural space, leading to lung collapse with a visible pleural line and absent lung markings beyond it. In cases of tension pneumothorax, mediastinal shift and lung compression may suggest haemodynamic compromise. It can be spontaneous, either primary (typically from subpleural bullae rupture in young, thin individuals) or secondary (most commonly due to COPD), or traumatic. [1]

4. Cardiac

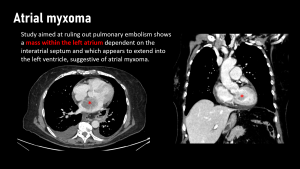

- Atrial myxoma

It is the most common cardiac tumour (25-50%) and occurs around the age of 50. It is an intracavitary tumour, attached to the endocardium by a small pedicle, usually dependent on the interatrial septum or the fossa ovalis. Seventy-five percent are located in the left atrium, 20% in the right atrium and rarely in the ventricles. [1]

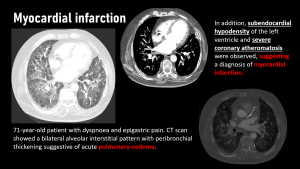

- Ischemic

It is an incidental pathology in radiological studies, as it is mostly diagnosed and managed in cardiology. It may be found in suspected pulmonary thromboembolism, requiring careful assessment of the myocardial walls, looking for irregularities or areas of hypocaptation. [1]

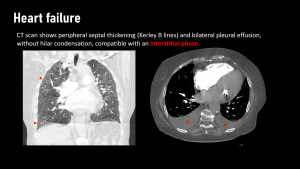

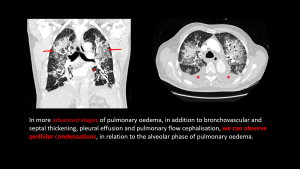

- Heart failure

It may be a ‘mimic’ of pulmonary thromboembolism, and could also be associated with elevated D-dimer, so clinicians may be asked to rule it out.

Imaging shows bilateral perihilar thickening with bronchial wall thickening, Kerley's lines and pleural effusion. [1]

- Cardiac tamponade

It is diagnosed with echocardiography, although it may be necessary to complete the study with CT to try to identify its aetiology. The image generally shows densitometric values of fluid and, depending on its volume, some collapse of the cardiac cavities can be observed. [1]

5. Vascular

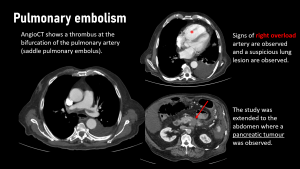

- Pulmonary embolism

99% of pulmonary embolisms are thrombi, however, there is a small percentage of non-thrombotic embolisms, such as fat particles, septic origin, amniotic fluid, air or foreign bodies (vertebroplasty cement for example). 90% of those of a thrombotic nature originate in the lower limbs. [1]

In addition, it is important to rule out other findings such as: [1]

- Pulmonary haemorrhage (due to reperfusion of the ischaemic area), in the form of ground-glass areas

- Atelectasis secondary to surfactant alterations due to ischaemia

- Pulmonary infarcts, in the form of peripheral triangular condensations that do not capture contrast

- Right overload, in the form of dilatation of the right ventricle or rectification of the interventricular septum

6. Others

- Massive ascites

Massive ascites can cause dyspnoea by compressing the diaphragm and limiting lung expansion. This displacement reduces lung volume, making breathing difficult. Imaging, typically via ultrasound or CT, reveals fluid in the peritoneal cavity, often shifting abdominal organs upwards and compressing the lungs. On CT, the fluid appears as a low-density area, potentially causing basal atelectasis and displacement of thoracic structures. [1]