CMBs are seen as punctate hypointense lesions without surrounding oedema, best detected on susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI).

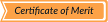

* Chronic small vessel disease

Hypertensive microangiopathy

Hypertensive microangiopathy is the most common cause of CMBs and reflects chronic damage to small penetrating arteries related to long-standing arterial hypertension. It is frequently associated with other manifestations of cerebral small-vessel disease and has important prognostic implications. [1]

Imaging features:

- Punctate hypointense foci on SWI, without surrounding oedema

- Predominantly deep distribution

- Basal ganglia

- Thalami

- Brainstem

- Cerebellum

- Often associated with:

- White matter hyperintensities

- Lacunar infarcts

- Generalized brain atrophy

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is caused by amyloid-β deposition within cortical and leptomeningeal vessels and is a major cause of lobar haemorrhage and CMBs in elderly patients. Its recognition is clinically relevant due to the increased risk of recurrent haemorrhage and implications for antithrombotic therapy. [1]

On imaging:

- Punctate hypointense foci on SWI

- Lobar and cortico-subcortical distribution

- Relative sparing of:

- Basal ganglia

- Thalami

- Brainstem

- Frequently associated findings:

- Cortical superficial siderosis

- Lobar intracerebral haemorrhage

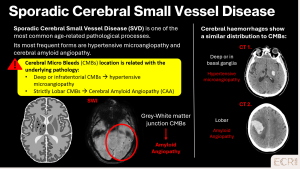

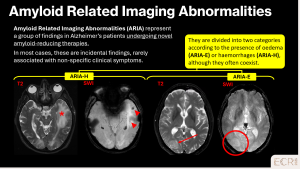

Inflammatory cerebral amyloid angiopathy (iCAA) and amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) represent distinct entities within the spectrum of CAA, both related to amyloid-β deposition in cortical and leptomeningeal vessels but with different pathogenic mechanisms and clinical implications.

> Inflammatory CAA

iCAA is an immune-mediated variant of CAA characterised by an inflammatory response against amyloid-β deposited in cortical and leptomeningeal vessels. It typically presents with subacute neurological deterioration, including cognitive decline, seizures or focal deficits, and is clinically relevant because it may respond to immunosuppressive treatment. [2]

Imaging features:

- Lobar CMBs on SWI

- Asymmetric vasogenic oedema on T2/FLAIR

- Cortical and cortico-subcortical involvement, often extending beyond a single vascular territory

- Variable contrast enhancement

- Possible associated cortical superficial siderosis

> Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities

ARIA are treatment-related imaging findings observed in patients receiving anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease. ARIA is subdivided into ARIA-E (oedema) and ARIA-H (haemorrhagic changes), the latter including CMBs and superficial siderosis. [2]

- ARIA-H

- New or increased lobar CMBs on SWI

- Cortical superficial siderosis

- Predominantly cortical or cortico-subcortical distribution

- ARIA-E

- Vasogenic oedema on T2/FLAIR

- Cortical and subcortical involvement, often asymmetric

- Possible mild mass effect

* Ischaemic and thromboembolic causes

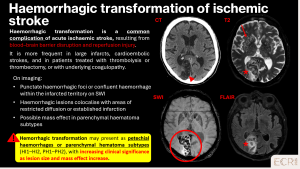

Haemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke

Haemorrhagic transformation occurs when reperfusion follows ischaemic injury, leading to microvascular leakage and petechial haemorrhages. [3]

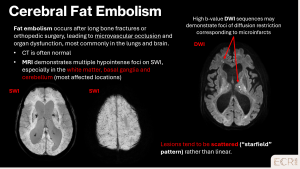

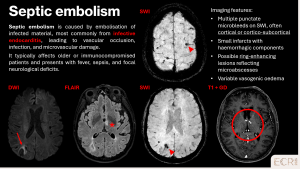

Embolic causes

CMBs may result from various embolic events, including endovascular procedures, fat, septic, or gaseous embolism. Patient history, including recent interventions, trauma, or infections, is essential to identify the underlying source and guide management. [1]

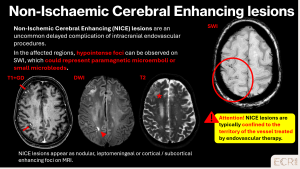

Non-ischaemic cerebral enhancing (NICE) lesions

NICE lesions are rare post‑endovascular complications caused by microembolisation of catheter materials, leading to focal endothelial injury, microvascular inflammation, and petechial haemorrhages. [4]

Imaging features:

- Punctate enhancing foci on post-contrast MRI, often within the treated vascular territory

- T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense, with microhaemorrhages on SWI

- Minimal or mild vasogenic oedema; diffusion usually not restricted

* Vascular

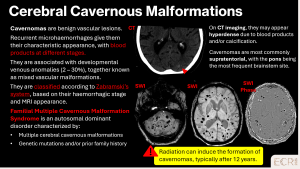

Cavenous malformations

> Sporadic cavernomas

Sporadic cavernomas are low-flow vascular malformations composed of dilated capillary channels, generally solitary and asymptomatic. [1]

>Familial multiple cavernomas

Familial multiple cavernomas are a genetic vascular malformation disorder, often inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. Patients may present with seizures, focal neurological deficits, or be asymptomatic, with microbleeds representing chronic small haemorrhages from cavernous malformations. [1]

Imaging features:

- Multiple punctate or “popcorn-like” hypointense foci on SWI, often with mixed signal on T1/T2 reflecting blood products of different ages

- Predominantly supratentorial, but brainstem and cerebellar involvement is common

- Typically no surrounding oedema unless recent haemorrhage has occurred

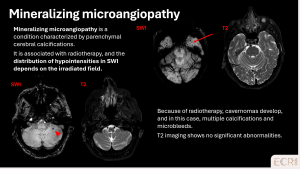

Mineralizing microangiopathy

Mineralizing microangiopathy is an acquired, post-radiotherapy small-vessel complication. It typically presents with punctate microbleeds on SWI in previously irradiated regions, sometimes associated with subtle white matter changes. [1]

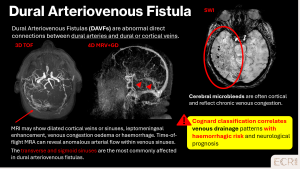

Dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAFVs)

DAFVs are acquired connections between dural arteries and venous sinuses or cortical veins. They may present with headache, tinnitus, or focal deficits. Cortical or subcortical microbleeds on SWI indicate prior haemorrhage, often associated with cortical venous reflux. [5]

Cerebral vasculitis

Cerebral vasculitis involves inflammation of small and medium sized vessels, causing multifocal microbleeds, infarcts, and white matter changes. Early recognition is critical for immunosuppressive therapy. [6]

On imaging:

- Multiple punctate hypointense foci on SWI, often cortical and subcortical

- May coexist with small infarcts or leukoencephalopathy

- Distribution is multifocal and asymmetric

* Traumatic

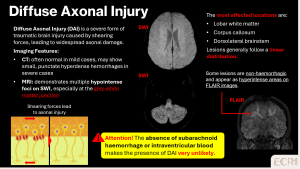

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI)

Diffuse axonal injury is a severe form of traumatic brain injury caused by rotational and acceleration–deceleration forces, leading to widespread axonal disruption. The corpus callosum is one of the most commonly affected structures, particularly the splenium, due to its central location and dense white matter composition. Callosal involvement is associated with severe trauma and poor neurological outcome. [1]

Imaging features:

- Punctate or linear lesions within the corpus callosum, classically involving the splenium

- Restricted diffusion on DWI in the acute phase, reflecting axonal injury

- Variable haemorrhagic components on SWI

Diffuse vascular injury (DVI)

DVI is a traumatic microvascular pathology that results from high-energy acceleration-deceleration forces applied to the brain. Although historically grouped with DAI, recent evidence suggests that axonal and vascular lesions have distinct pathological responses to tissue deformation and often occur in differing regional patterns rather than complete overlap. [7]

DVI reflects traumatic damage to blood vessels and capillaries with consequent petechial haemorrhages and microvascular disruption, whereas DAI represents mechanical shearing of axons. The two often coexist in severe blunt force trauma, but they each contribute independently to injury burden and clinical outcome.

On imaging:

- SWI: numerous punctate haemorrhages throughout the white matter, not confined to classic DAI locations

- Minimal diffusion restriction

- CT is often normal

> Differentiating DVI from DAI:

- DAI is characterised by microhemorrhages and non-haemorrhagic lesions along typical white matter tracts such as the splenium of the corpus callosum, brainstem and parasagittal regions, with prominent acute restricted diffusion.

- DVI shows more widespread punctate haemorrhagic lesions that are less associated with diffusion restriction and may occur in regions not typical for axonal shearing.

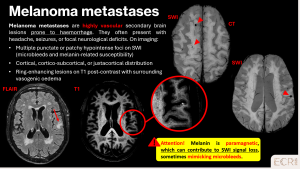

* Tumoral

Metastases

Haemorrhagic-prone metastases, such as those from renal cell carcinoma or melanoma, can cause CMBs. These are typically cortical or cortico-subcortical in distribution and may coexist with larger metastatic lesions or post-radiosurgery changes. Vasogenic oedema is usually minimal. [1]

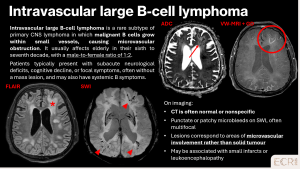

Primary CNS lymphoma (intravascular large B-cell type)

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma is a rare subtype of primary CNS lymphoma characterised by malignant lymphocytes within small vessels, leading to microvascular obstruction and microbleeds. [8]

* Infectious

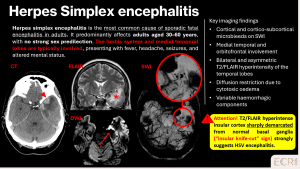

Herpes simplex virus encephalitis

HSV encephalitis is a severe viral infection, classically affecting the medial temporal lobes and orbitofrontal regions. Clinical presentation includes fever, headache, seizures, and altered mental status. [9]

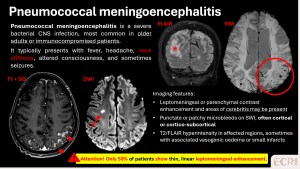

Pneumococcal meningoencephalitis

Severe bacterial infection can lead to microvascular damage and CMBs. Patients often present with fever, neck stiffness, altered consciousness and signs of sepsis. [10]

* Systemic causes

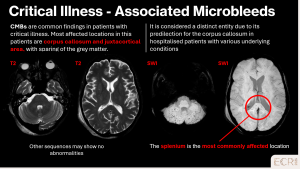

Critical illness-associated microvascular damage

Severe critical illness, including sepsis, respiratory failure, or multi-organ dysfunction, can result in widespread microvascular injury in the brain. The underlying mechanisms include endothelial dysfunction, hypoxia, systemic inflammation, and coagulopathy, which together lead to small vessel disruption and petechial haemorrhages. Clinically, patients may present with altered mental status, delirium, or diffuse neurological deficits, although findings can be subtle. [1]

Radiological findings:

- Numerous punctate hypointense foci on SWI, often diffuse and involving both cortical and deep regions

- May be associated with leukoencephalopathy, small infarcts or chronic microvascular changes

- Surrounding oedema is typically minimal or absent

- CT is often normal or shows only nonspecific hypodensities

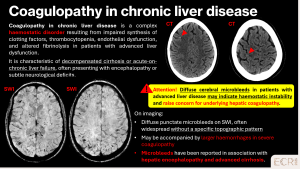

Coagulopathies in chronic liver disease

Patients with chronic liver disease may develop coagulopathies leading to CMBs. These result from impaired synthesis of clotting factors, thrombocytopenia, and fragile microvasculature. [11]

* Genetic diseases

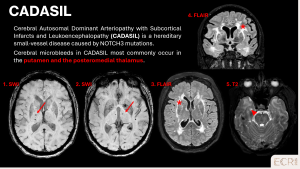

Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL)

CADASIL is an inherited small-vessel disease caused by NOTCH3 mutations, leading to recurrent microvascular injury, lacunar infarcts, and cognitive decline. Patients often present with recurrent lacunar strokes, migraine with aura, mood disturbances or early cognitive decline. [1]

Imaging features:

- Deep and periventricular punctate hypointense foci on SWI

- Frequently associated with white matter hyperintensities and lacunar infarcts

- Predominantly affects basal ganglia, thalami, brainstem and temporal lobes

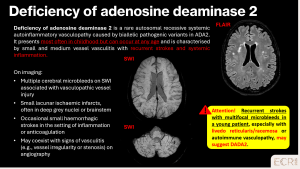

Deficiency of Adenosine Deaminase 2 (DADA2)

DADA2 is a rare autosomal recessive vasculopathy caused by ADA2 mutations. It typically affects children or young adults, presenting with recurrent strokes, systemic inflammation, and sometimes livedo reticularis/racemosa. Imaging may show multiple CMBs, small lacunar infarcts, and features of small / medium vessel vasculitis. [12]