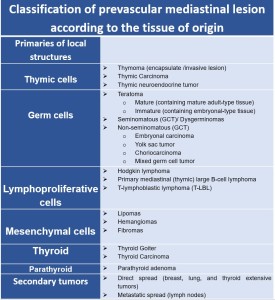

Tumors found in the prevascular mediastinum are either primaries of local structures i.e. thymic tumors, germ cell tumors, lymphomas, mesenchymal tumors, ectopic thyroid and parathyroid tumors, or secondary tumors by direct or metastatic spread, more commonly from lung, breast or thyroid tumors.

While CXR usually raises the question of mediastinal mass and MRI solves tissue-specific problems, CT plays a key part in characterizing and differentiating the source of a lesion due to its spatial resolution, readiness, and availability; hence, it was our main focus.

We evaluated tissue characteristics of the lesions, location, and anatomic relationships in an attempt to recognize typical from atypical behavior, in various clinical onsets and presentations.

For a better understanding of the prevascular mediastinal lesions, CT analysis should be systematic and should address multiple characteristics, including:

- location, size, morphology, and margins;

- density/attenuation and enhancement characteristics;

- presence or absence of lymphadenopathy;

- relationship with adjacent structures, including mass effect and/or invasion.

To clarify the findings, the lesions were classified primarily according to their density/attenuation, and the other CT characteristics described above were detailed for each case.

Fat-containing lesion:

Fat-containing masses feature densities between -40 and -120 HU on CT. The most common lesion is mature teratoma, a heterogenous benign neoplasm with components of varying attenuation (fat, fluid, soft tissue, calcium, and fat-fluid level) [2].

A mass with a purely fat attenuation may suggest a rare thymolipoma or lipoma.

Pitfalls: A purely fat mass in the prevascular mediastinum can be confused with a fat pad or anterior hernia (Morgagni hernia). To avoid this pitfall, it is important to visualize the coronal and sagittal images, which can depict the absence of a portion of the diaphragm and vessels originating below it. Clinical presentation is essential, while Morgagni hernias are usually asymptomatic, necrosis of the fat pad may present with chest pain. [3]

Cystic Lesions:

Pure cystic lesions are benign structures with a CT density between 0 and 20 HU, frequently thymic or pericardial cysts. Other cystic lesions are teratomas with a predominantly cystic component.

Thymic cysts may be either congenital or acquired. They are spade-shaped structures localized in the thymic bed. Congenital thymic cysts are generally unilocular and contain clear fluid and are found incidentally in patients during the first 2 decades of life, while the acquired ones may be multilocular and contain heterogeneous fluid indicating a high protein content (due to infection of hemorrhage) [4].

Cystic lesions containing internal soft tissue components and/or internal septations include multilocular thymic cysts, cystic teratoma, lymphangioma, and cystic thymoma.

Pitfalls:

- Thymic cysts can be misinterpreted as solid masses when their attenuation is higher than expected for fluid (above 20 UH) how it is, for example in acquired cysts. For the differential diagnosis is important to know the conditions associated with acquired thymic cysts including neoplasms, radiation therapy, thoracotomy, and chest trauma. Given the difficulty of a differential diagnosis, is important to consider MRI in distinguishing true cystic from solid lesions. [4]

- Morgagni hernia in a patient with ascites can appear as a cystic lesion in a prevascular mediastinum on a CT scan.

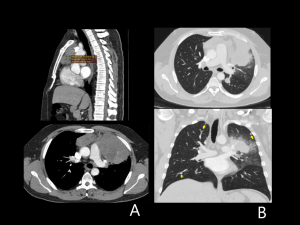

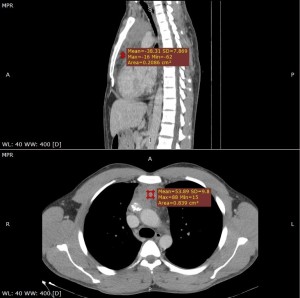

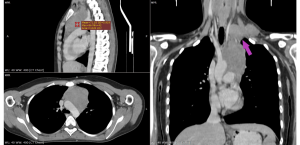

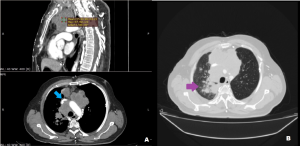

Fig 5: Contrast-enhanced CT- venous phase images of 42-year-old men reveal an anterior diaphragmatic defect with the presence of fluid in the hernial sac - suggestive appearance of a Morgagni hernia. Purple arrow – defect of the diaphragm, red arrow – compression of the adjacent pulmonary parenchyma. References: Department of Radiology,” St. Spiridon” Hospital, Iasi, Romania

Fig 5: Contrast-enhanced CT- venous phase images of 42-year-old men reveal an anterior diaphragmatic defect with the presence of fluid in the hernial sac - suggestive appearance of a Morgagni hernia. Purple arrow – defect of the diaphragm, red arrow – compression of the adjacent pulmonary parenchyma. References: Department of Radiology,” St. Spiridon” Hospital, Iasi, Romania

Soft tissue lesions

- Thyroid Goiter/ Thyroid malignancy

A mediastinal goiter is a heterogeneous mass that extends from the cervical thyroid gland into the anterior or superior mediastinum. Rarely, mediastinal goiters can also occur from ectopic thyroid tissue.

On CT scans it presents as an encapsulated and lobulated mass with a high attenuation value relative to adjacent muscles (70-85 HU) before the contrast administration, because of the presence of iodine, and a prolonged and sustained enhancement is visible after IV contrast administration. Thyroid cancer has similar features but with ill-defined margins, invasion of the adjacent structure, and enlargement of the lymph node.[4]

- Thymic Epithelial Neoplasms include thymoma, thymic carcinoma, and thymic neuroendocrine tumors.

- Thymoma is the most common prevascular mediastinal mass, especially after the age of 40 without gender predilection. It presents as a well-defined mass with uniform soft-tissue attenuation on CT, typically located anteriorly of the aorta in the superior mediastinum. Large lesions associate areas of cystic or necrotic degeneration, often accompanied by calcifications within the capsule or scattered throughout the mass, indicating invasive thymoma. The preservation of a well-defined fat plane between the thymoma and adjacent structures is a sign of benignancy. Lymphadenopathy is typically absent. [5]

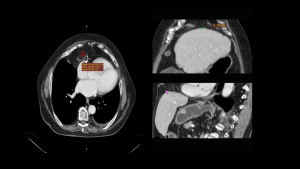

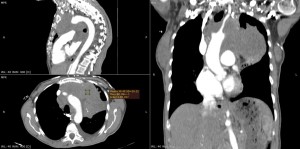

Fig 7: Contrast-enhanced CT- arterial phase, 75-years old man: a round, well-defined lesion in the prevascular mediastinum with uniform soft-tissue attenuation, suggestive of thymoma. References: Department of Radiology,” St. Spiridon” Hospital, Iasi, Romania

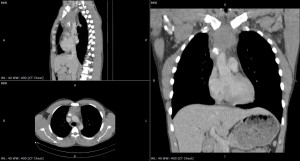

Fig 7: Contrast-enhanced CT- arterial phase, 75-years old man: a round, well-defined lesion in the prevascular mediastinum with uniform soft-tissue attenuation, suggestive of thymoma. References: Department of Radiology,” St. Spiridon” Hospital, Iasi, Romania Fig 8: Contrast-enhanced CT venous phase images,18-year-old woman: soft-tissue heterogeneous lesion localized in the prevascular mediastinum, well-defined, with mild enhancement - thymoma. References: Department of Radiology,” St. Spiridon” Hospital, Iasi, Romania

Fig 8: Contrast-enhanced CT venous phase images,18-year-old woman: soft-tissue heterogeneous lesion localized in the prevascular mediastinum, well-defined, with mild enhancement - thymoma. References: Department of Radiology,” St. Spiridon” Hospital, Iasi, Romania - Thymic carcinoma usually causes loss of the fat plane between the mass and adjacent mediastinal structures, with extension into the mediastinum or lung parenchyma. Drop metastases are pleural deposits (especially posteriorly and in the costophrenic angles), determining irregular pericardial thickening. [6]

- Thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms are the least common primary thymic tumors, usually carcinoids. On CT, they typically present as invasive soft tissue masses often associated with mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Though CT features are not characteristic, association with a paraneoplastic syndrome, most commonly Cushing syndrome, may suggest diagnosis. Biopsy or surgical resection is required.

Pitfalls: Thymic hyperplasia can be easily confused with thymoma. Thymic hyperplasia is a diffuse, symmetric enlargement of the thymus, scattered fat and soft-tissue elements, and a smooth contour with preserved adjacent fat planes. There was slight or no enhancement noted in thymic hyperplasia. All thymic hyperplasia cases present as quadrilateral, triangular, or bilobed in shape. Clinical context plays an essential role in differential diagnosis. Thymic hyperplasia occurs typically in patients with systemic disorders, such as myasthenia gravis, collagen vascular disease infection, etc. After hormonal treatment, the hyperplastic thymus often atrophies and may return to previous dimensions when treatment is discontinued. [4]

- Lymphoma

Lymphomas are the second most common cause of prevascular mediastinal mass in adults.

Mediastinal lymphomas may involve the thymus, mediastinal lymph nodes, and/or mediastinal organs (i.e. lungs, pleura, heart, pericardium).

Mediastinal lymphoma can be primary or secondary. CT reveals lymphadenopathy and/or lobulated soft tissue mass in the prevascular mediastinum with homogeneous soft-tissue attenuation, irregular border, absence of vascular involvement, and mild-moderate contrast enhancement. Necrosis or hemorrhage may occur, causing heterogeneous attenuation. Another characteristic feature of the lymphomatous masses is that they tend to displace and encase mediastinal structures, rather than narrowing or invading them. The masses can invade the superior vena cava and the left brachiocephalic vein.[6] [2]

Mediastinal lymphomas may become very large and are known as bulky diseases if the cross-sectional diameter of the mass is more than 10 cm or more than 1/3 of the cross-sectional diameter of the thorax. [4]

These imaging features in combination with clinical information such as B symptoms (fever, weight loss, and night sweats) can strongly suggest the diagnosis.

Pitfalls: Calcification

Calcification can provide valuable diagnostic clues in mediastinal lesions but can also be a pitfall. Lymphomas usually don’t show calcification, but after radiation therapy, 5% of these lesions may present calcifications.[3]

- Non-teratomatous Germ Cell Tumors

Malignant tumors occur in young males and most frequently affect the anterosuperior mediastinum. The tumors grow rapidly and develop large, bulky, ill-circumscribed masses with lobulated shape. On CT scan, the tumors have a homogenous appearance and show minimal contrast enhancement. Areas of degeneration due to hemorrhage and coagulation necrosis may be present. NSGCT should be considered when a heterogeneous prevascular mass is present with lung metastases on CT in young men 10-39 years of age. [7], [8]

Regarding the relationship with adjacent structures, due to the absence of anatomic border between the mediastinal compartment, pathologic processes can spread unchecked from one compartment to another. Therefore, the diagnosis can be challenging, and potential pitfalls may arise.